At the Movies: And the Band Played On (1993)

A disaster revisited

This is the second post in a short series on gay-themed film that was supposed to have a few more entries before June got away (read the first entry here, on the British film Victim). Ironically, working on my own first major screenplay made the month evaporate. But if you’re a paid subscriber, please enjoy this and any subsequent late entries, with apologies. If you’re not a paid subscriber and you missed the last sale on annual subscriptions, they’re now going for $40/year. This unlocks all paid archives plus a nice little handful of exclusive posts each month. Meanwhile, I’m slowly organizing my archives by tag so that I can easily link to everything I’ve written in a given category. If you’re interested in more of my writing on gay history, click here. If you’re interested in more of my writing on movies, click here. As always, thanks for your continued readership!

AIDS did not just happen. It was allowed to happen. This is the thesis Randy Shilts undertook to defend in his 1987 book And the Band Played On. Running over 600 pages including notes, it remains the seminal journalistic chronicle of the epidemic. It was many books in one book: a medical thriller, a political hand grenade, a human interest story—or, rather, dozens on dozens of overlapping human interest stories. In some circles, it made Shilts a star. In others, it made him a pariah. Some would even call him a traitor to “his own kind”: gay men.

Nobody could have mistaken Shilts for a conservative journalist, nor could And the Band Played On be mistaken for a conservative book. Fundamentally, it’s an anti-establishment book, and as such, it takes aim at many conservative establishments. But its great crime, for some readers, was that it was consistently anti-establishment—including the gay establishment. Shilts justified this with a vivid metaphor: To wink at gay men’s own role in spreading the disease would be “like going to one side of a burning building and covering the firemen trying to put out the fire, and then ignoring the guy on the other side who’s dumping gas on it.”

This resentment still festers to this day, as we saw during last year’s monkeypox outbreak. Officials hesitated to make the obvious recommendations out loud, and those who did tended to be shouted down by a chorus of angry voices asking “if we had learned nothing from the AIDS epidemic.” Few people were bold enough to toss the question right back. Sadly, Randy Shilts wasn’t available for comment, having died of AIDS himself in 1994.

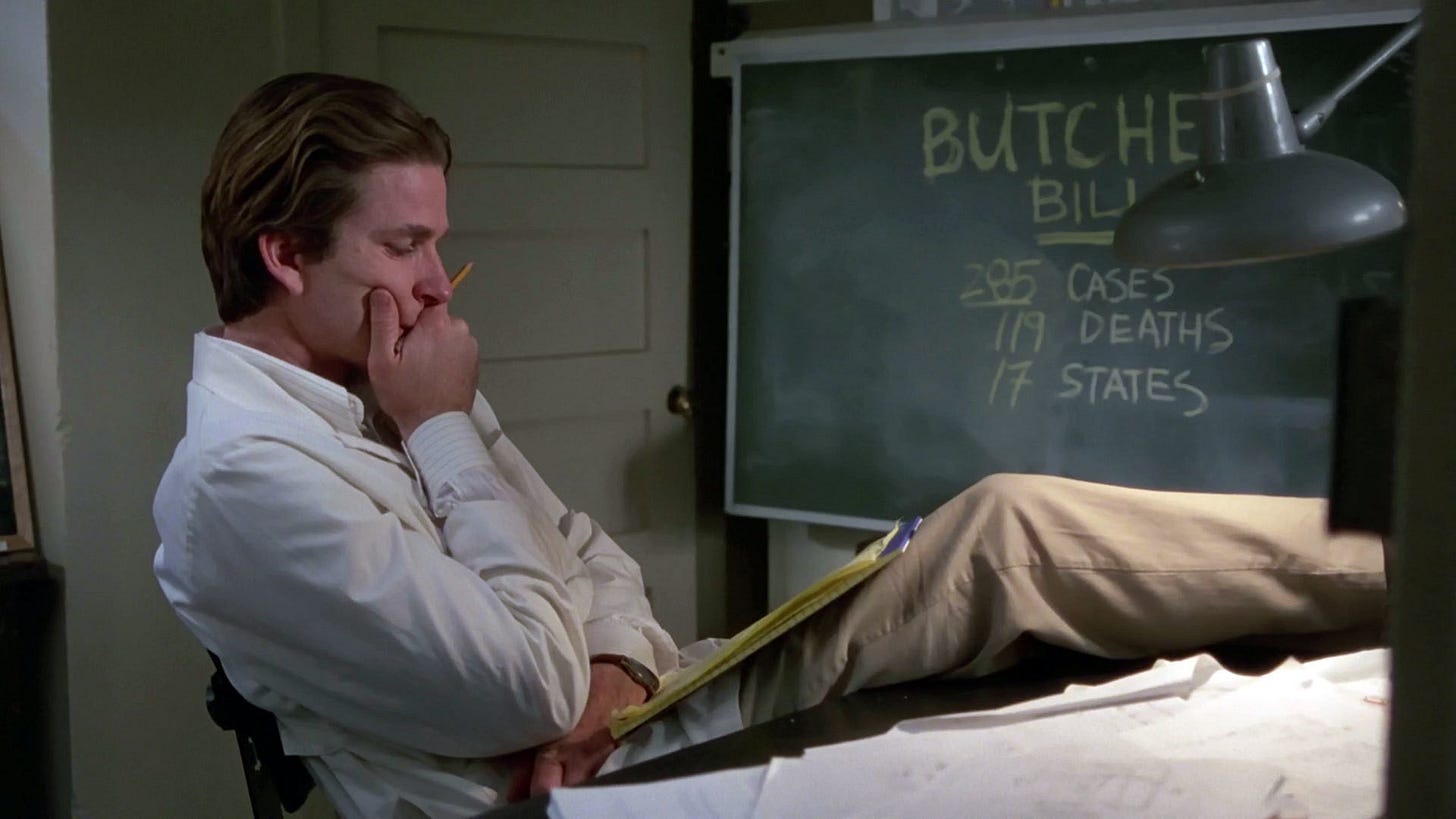

This year marks the 30th anniversary of HBO’s adaptation of the book, released barely in time for Shilts himself to see it. The casting took an approach reminiscent of old ensemble pieces like WWII drama The Longest Day, giving lesser-known actors most of the screentime while big names like Steve Martin and Richard Gere made brief cameo appearances. For its protagonist, it wisely chose to focus on Dr. Don Francis (Matthew Modine), the prodigious young epidemiologist who had already helped to eradicate smallpox and develop a hepatitis B vaccine before studying AIDS. On the cusp of the new pandemic, we follow him and his small task force as they frantically rush out onto the train tracks waving red flags, only to realize with dawning horror that the train isn’t slowing down. It’s speeding up.