Carved With Pride

On Memorial Day

My childhood was unusually defined by radio. We didn’t have cable, so the time other kids spent watching television was time I spent listening to kids’ radio programs. My favorite was a particularly long-running, popular show called Adventures in Odyssey, a small-town sitcom in evangelical Christian perspective. It wasn’t high art, but it was clever and earnest and well-presented. Among other wholesome things it gave me, various episodes instilled a healthy respect for American veterans. The writers weren’t interested in complexifying simple values like patriotism, duty, and courage, for which in hindsight I’m grateful. I was a child, and I didn’t need this stuff to be complicated. More nuance would come later, but it was important that my foundation was laid without cynicism.

The show first aired in 1987, when Vietnam was still a fresh wound and World War II was still within living memory for the fictional town’s wise older characters. Several throwback episodes revisited those memories, Old Hollywood style. But the couple episodes handling Vietnam had a different flavor. They didn’t give the listener a “worm’s-eye view” of the Vietnam conflict. The writers knew there would be no good way to do this without making the show too grim for a child. Instead, they explored the memories of the families left behind—the man whose big brother chose not to dodge the draft, the widow whose husband didn’t live to meet his son.

Even these episodes, sad as they were, remained consistently patriotic. The noble big brother, modeled on the writer's own brother, is contrasted in memory with a scruffy, draft-dodging hippie friend. The widow delivers a stirring Memorial Day speech pushing back on the anti-war sentiment her son has encountered in school. The take-home message is that however messy the conflict, honor and courage still mean something, should still be memorialized.

I still believe in that message. And yet, in revisiting the episode about the war widow this weekend, I couldn’t help feeling sympathy for the character of the teacher who gives his student an anti-Vietnam book. Unaware that the student’s mother is a war widow, he launches into a bit of heavy-handed dialogue about how all the soldiers “went over there and died for nothing,” or worse, became murderers. The town’s father figure, a World War II veteran, later pays a visit to chide the teacher for the damage he’s unknowingly caused. Predictably, it emerges that the teacher lost a brother in the war. One really feels sorry for everyone in the story—both the teacher whose grief is inevitably mixed with anger and the boy now haunted by dreams where his father is accused of being a murderer.

There’s a philosophy of war within which even though the boy’s father was not a murderer, he was still, in some sense, indirectly complicit in murder. By participating in the system, in the “machine,” he still struck a terrible bargain. He became a cog in a wheel. He lost himself. Then he died, for nothing.

The episode rejects this philosophy to place the focus back on the individual soldier, the individual honorable man who lives and dies with his own hands clean. By Memorial Day, the son has lost his appetite for battle reenactments. So, for the first time, his mother stands up and reads her husband’s last letter, where he anticipates what will be written about the war in future years. He can only write from what he has seen and done, and all he’s ever seen and done has been about fighting evil and protecting the innocent. These are the memories he shares. This is the legacy he leaves.

But I still understand that teacher. I understand him, because I hear in his voice the same dull ache that I hear in the voices of my own generation. Like the war writer Phil Klay in this essay passage about visiting the graves of 90s kids at Arlington, he can’t simply grieve. He can’t simply memorialize:

Their mission, we were told, “will not involve American combat troops fighting on foreign soil.” They would conduct “supervise, train and assist” missions. They wouldn’t constitute “boots on the ground.”

So when they die, our government does what former defense secretary Robert Gates calls “semantic backflips” to avoid saying that our troops are in combat. At a recent press conference where journalists repeatedly asked the Pentagon press secretary whether or not we were “in combat,” he had the unenviable job of explaining that, well, they’re “in harm’s way” or “in combat situations,” or “they have found themselves under fire.”

Such evasions grate on me, especially around Memorial Day. This year’s war dead—nine so far—didn’t slip, trip, and find themselves in combat. We sent them there to fight a war on our behalf, whether we like to acknowledge that or not. They went, they fought, and they died.

So my sadness this weekend, the same sadness I felt walking through Arlington, is mixed with something else. I can’t simply reflect on the dead of my war. I can’t simply memorialize.

Last year, I had a high school student who was very earnestly considering a career in the Marines. He talked quietly about the videogames he’d grown up on, the things he looked up to in veterans, the longing to experience the brotherhood of war. A gentle, thoughtful kid. Privately, I hoped he would take a different path. When he decided to go to trade school instead, I breathed a sigh of relief.

There’s a cliché that only two men ever died for you: Jesus Christ and the American soldier. Growing up, I heard and earnestly loved a number of very well-meaning songs built on that premise. Later, I came to feel an unease around them—not because my respect for the dead American soldier had grown any dimmer, but because my understanding of his death had grown sadder. Because he wasn’t Jesus, and because his wasn’t the blood that could take away the sins of the world, or the nation.

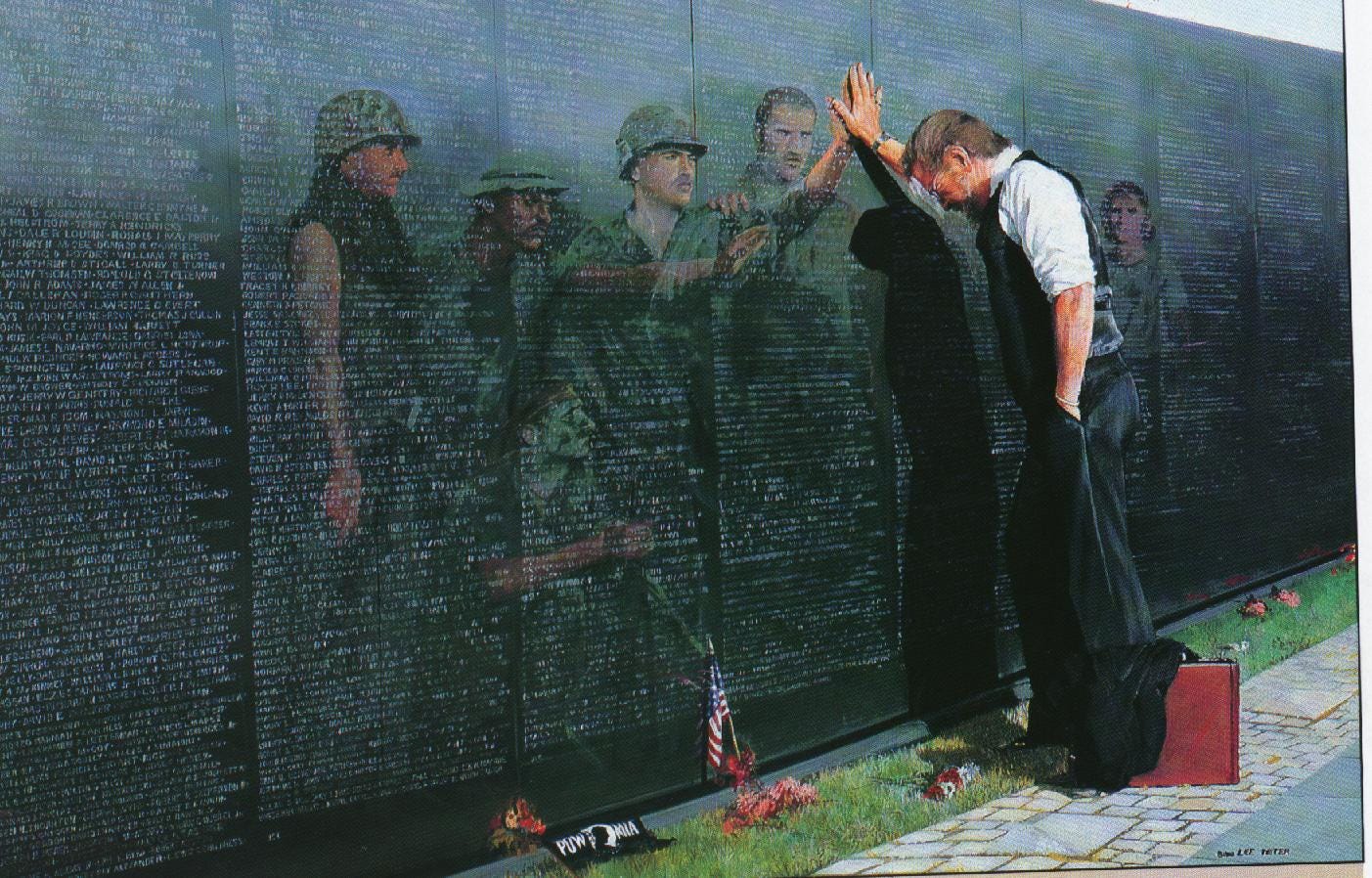

Did the soldiers of Vietnam die for nothing? Did the soldiers of my war, and every other sad, murky, messy war we’ve ever tried to fight, die for nothing? How do you answer these things, quantify them? And as you try to answer, how do you look the widow in the eye, and the widow’s son?

To do this, you would have to define “nothing.” And “something.” And in trying to do this, you would find that there is no one way to do this. A man enters a war of dubious origins, with dubious outcomes. He does what he can. He loves his family. He loves his brothers in arms. One day, he gives his life for them. Is that “nothing”? He didn’t have to fight this war. It was not a necessary war. It was not a necessary death. It was a death that, through another career choice, could have been avoided as honorably as it was embraced. But was it “nothing”?

Perhaps not, in his case, because his death had meaning through sacrifice. But what of the soldier who’s robbed of such meaning in death, who never does anything heroic, unless one counts the simple act of risking a meaningless death? What of him?

We remember him. Today, we remember him. That is all we can do.

You have the ability to help us feel the ache of humanity in this fallen world, and this is a really good example of that gift.

When you write, "that is all we can do" it does not feel like quitting or cowardice, it feels human.

Thank you for writing this, you express the thoughts of many. Currently my son serves in the military so Memorial Day is weighed down with the possibility of him being in that number. I honor the dead with trepidation for the ones to follow.