Feynman and the Bomb

After Hiroshima

Today marks the 80th anniversary of the atomic destruction of Hiroshima. To mark the occasion, Pope Leo in his weekly audience delivered a critique of nuclear deterrence, expressing his hope that “in the contemporary world, marked by strong tensions and bloody conflicts, the illusory security based on the threat of mutual destruction will give way to ... the practice of dialogue.” Hiroshima (and Nagasaki) stand to this day “as a universal warning against the devastation caused ... by nuclear weapons.” In a similar vein, a delegation of Catholic bishops to the city have issued a joint statement strongly condemning “the use and possession of nuclear weapons and the threat to use nuclear weapons.”

My own (in my broad tribe, unpopular) view is that our deployment of the bomb was a war crime. I do not believe the end of finishing the war justified the means of unleashing a weapon that instantly vaporized 78,000 civilians (including Christians, a precious surviving remnant after years of brutal suppression, as depicted in Japanese literature like Silence).

With that said, now that the bomb exists, my thoughts on deterrence are more complicated. For now, I’m settled on the view that it’s unwise to dismantle our program as long as countries like China, Iran, Russia, etc., exist. It’s rather a paradox, I admit: To actively use our arsenal, I maintain, is immoral, and yet I don’t think it’s necessarily immoral to passively leave it undestroyed. Maybe I could be persuaded out of this view. I’d be interested to know how common (or uncommon) it is.

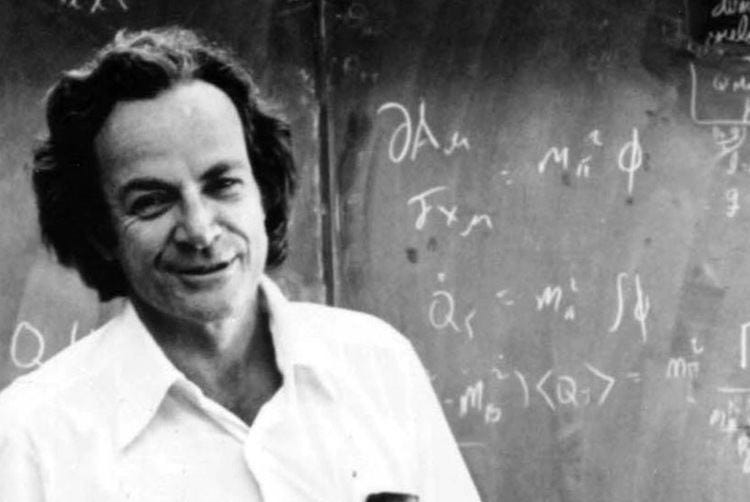

Meanwhile, I’ve been marking the occasion in my own way by revisiting one of my favorite memoirs, Richard Feynman’s Surely You’re Joking, Mr. Feynman. Feynman was a very young scientist when he was hired to join the team at Los Alamos. After the war, he went on to establish himself as a brilliant lecturer, raconteur, and all-round maverick. He appears as a character in a few scenes from the movie Oppenheimer, including the Trinity test, which he insisted on trying to watch from inside a car without protective glasses, because he was kind of an idiot like that.

Feynman described the test in a few remarkable pages of Surely You’re Joking. In one sense, they’re no different from the rest of the memoir. He delivers the account in the same buoyant, almost boyish voice with which he relates all his memories (which sound more like dialogue than prose, because that’s the way they were originally recorded, set to tape and written down later). He doesn’t use the occasion to deliver any grand moral verdicts or make a political speech, because he was never a political animal. He’s just telling you what he saw.

But if the account is not ponderously moralistic, neither is it glib. After the test, he describes an encounter with a fellow scientist named Bob Wilson. Wilson is the man who came into Feynman’s office at Princeton one day and said “that he had been funded to do a job that was a secret, and he wasn’t supposed to tell anybody, but he was going to tell me because he knew that as soon as I knew what he was going to do, I’d see that I had to go along with it.” And he began to talk about this problem, the problem of how to separate different isotopes of uranium, which was on the way to the problem of how to make a bomb. “There’s a meeting…” he started to say.

Feynman said no. “All right,” Wilson said, “there’s a meeting at three o’clock. I’ll see you there.”

After Wilson left, Feynman started pacing and thinking. The Germans were working on this problem too, he thought. That thought frightened him. So he decided to go to the meeting.

Of course, by the time of the Trinity test, all eyes were on Japan, not Germany. The Pacific Theater had yielded some of the bloodiest battles of any war in our history. We were closing in. Yet, insanely, Japan refused to surrender. So, in Los Alamos, things proceeded according to plan. And after the successful test, the general mood was jubilant. Feynman sat on the end of a jeep and entertained everyone by playing the bongos (a nice Easter egg in Oppenheimer for the fans). There was plenty of alcohol to go around. Everyone was happy—except Bob Wilson. “What are you moping about?” Feynman asked. “It’s a terrible thing we made,” Wilson said.

Feynman could move on from this moment. Instead, he pauses to reflect—still not ponderously, but, in his own way, profoundly.

The rhythm of Feynman’s speech makes these pages feel a bit like dramatic monologue. This inspired me to see if they could be converted into a blank verse poem. Opinions will vary on how well I succeeded, but in the end, as with anything, I write for myself (aka my own harshest critic). So, while we’re thinking about bombs today, here it is:

Trinity

“The baby is expected on…” what date?

Let’s see, it was the 16th of July.

I flew right back as soon as it came through.

I got there just in time to miss a bus,

But that was fine. I knew where we would meet.

Our radio died (because of course it would),

And so we sat and played a guessing game

Out in that desert silence. Wait, wait, wait…

Until, through static, suddenly, the word:

It’s time. Just seconds left to go. Stand by.

Dark glasses? Geez, it’s twenty miles away.

I’ll never see the goddamned thing, unless

I’m sitting in a truck, windshield between

Me and the ultraviolet light I know

Could really blind me. But I have to see

The flash. Bright light can never hurt your eyes.

And then, oh Jesus, there it is! So bright,

I gotta duck. I see this purple splotch,

An after-image. That’s not it. Look up,

See white change into yellow into flame.

And then the ball of fire starts to rise,

Billow, get black around the edges. Now

You see it isn’t fire, it’s smoke. The fire’s

Inside, the flash, the burning white, the heat.

I’m telling you, I saw it all, just me

And my two human eyes. No one but me.

Then came the BANG, and then the thunder rolled,

And it was like we’d woken from a dream.

That night, we all began to celebrate.

I drank and whooped and beat my drums of war.

But then I saw Bob Wilson sitting there,

The guy who put me on this whole damn thing.

I asked why he was moping. And he said,

“We made an awful thing, Dick. You and me.”

“Don’t look at me,” I said. “You started it!”

But that was it, you see. ‘Cuz once you start

To do an awful thing for all the best

Of reasons, you stop thinking. You just stop.

Except for Bob. I guess he never stopped.

Our job was over. Everyone went home.

I got a nice position at Cornell.

And still I couldn’t shake the strangest thought.

Just looking out the window at New York,

I’d think about the radius of death.

How far was it from here to 34th?

Those buildings would be gone, and those, and those.

Those bridges they were building, smashed to bits.

“Useless,” I thought. “Why don’t they all just stop?”

But it’s been forty years now, so I guess

I figured wrong. I’m glad they never stopped.

Thanks for this—unflinching and capacious. You neither rush to condemn nor retreat into abstraction. What you call a paradox—keeping the arsenal without using it—might simply be the moral cost of not being naïve. Your reading of Feynman honors that same tension. He refuses the posture of sage, yet can’t shrug off consequence. The dramatic monologue works—because you let the poetry emerge from his cadence without forcing insight where he offers none. Bob Wilson, by contrast, keeps the conscience alive. His quiet protest doesn’t demand agreement, only attention. It's good to mark this day by listening to those who couldn’t forget.

"Don’t look at me,” I said. “You started it!”

But that was it, you see. ‘Cuz once you start

To do an awful thing for all the best

Of reasons, you stop thinking. You just stop.

Except for Bob. I guess he never stopped."

Lots of truth here.

In a way, nuclear weapons are a microcosmic example of how Original Sin matters and taints everything else. In this case, the original sin with nuclear weapons is developing working ones in the first place. You open Pandoras box or dig too greedily and awaken a Balrog.

That nuclear weapons got used is almost an afterthought in comparison to the problem of initial creation. Creating a situation where evil tools end up getting deployed in a defensive/stable arrangement highlights the fallenness of this world.

In the microbiological sphere, engineering pathogens (a la Demon in the Freezer) are doing similar things, as are to an even greater degree some of the engineering of embryos with more than two parents to name just two examples.