Giving Billy Joel His Due

The Piano Man has love, but he should get more respect

Parts of this article previously appeared in First Things.

I vividly remember the first time I heard Billy Joel on the radio. Mainstream pop/rock radio was not part of my childhood listening diet, so I was already in my early teens. I was having lunch in a university roadhouse with my father and a visiting scholar, a young neo-classical composer. We took turns poking fun at the songs on the roadhouse channel, until “Scenes From an Italian Restaurant” struck up. Then the composer paused to listen, raised a finger and said, dead serious, “This is a great song.”

I listened intently for the whole seven minutes. The composer occasionally dropped in a comment about what made it so good. I was intrigued. That night I went home and looked for the track on Last.fm (this was well before the days of Spotify). When I found it, I listened to it again. And again.

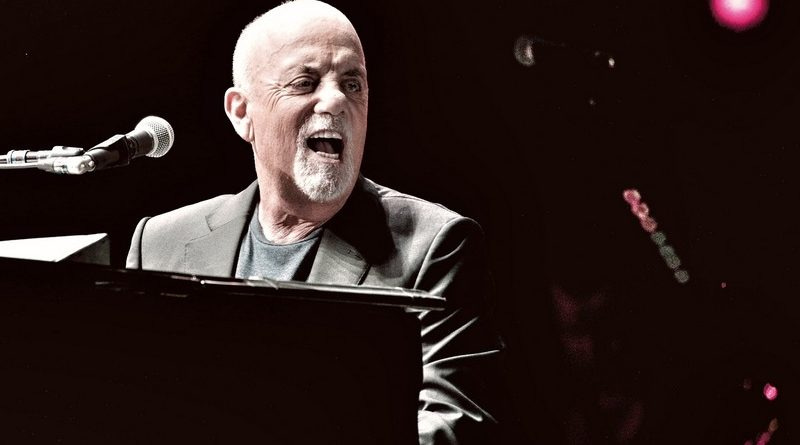

Decades later, the tune received a full music video treatment, a handsomely animated production in the style of a classic comic strip. That year (2021) marked Joel’s fiftieth in the business. Though he hasn’t released a full album of new music within my lifetime (well okay, technically River of Dreams came out when I was a few months old), he has remained a hot concert act. Last month, he played Madison Square Garden for the hundredth performance in a remarkable decade-long streak that will finally end this July. The landmark event was taped and aired on CBS, but through some glitch, the program cut off in the last few minutes. Fan outrage was so strong that the network is airing the whole concert again. His newest song, “Turn the Lights Back On,” also has a music video, which uses AI to create the illusion that fans are watching younger Billy morph into older Billy before their eyes. Some find it sweet. I find it faintly unsettling, though it is rather remarkable to hear how little his voice has really changed.

Yet, for all his loyal fan love, Billy Joel remains the Rodney Dangerfield of rock and roll: He don’t get no respect. Where records by the Boss, the Beach Boys, and others have been marked as watershed moments in rock history, Joel’s body of work is regarded as mostly “dead stock,” fit for little more than oldies radio, Long Island wedding karaoke, and boomer nostalgia TV. As Chuck Klosterman famously summarized for the Times, “He has no intrinsic coolness, and he has no extrinsic coolness. If cool were a color, it would be black—and Joel would be kind of a burnt orange. The bottom line is that it’s never cool to look like you’re trying . . . and Joel tries really, really hard.”

In fairness, Joel has often confessed that he dislikes his own voice. He always saw himself as primarily a writer, capable of tailoring a tune to any style, always imagining “What if so-and-so sang this?” “So-and-so” could be anyone from Sting to Gordon Lightfoot to the Righteous Brothers, as long as it wasn’t Billy Joel. But peers like Paul Simon disagreed. In a 1984 Playboy interview, Simon praised Joel’s voice and simply wished he would spend more time figuring out “who Billy Joel is.”

Joel once said he’d written “Scenes From an Italian Restaurant” while thinking of the high school guys he knew who “peaked too early.” Perhaps there was some wry self-recognition in this. Arguably, the smash success of “Just the Way You Are” set the course for eighties-era Joel to lose what he’d already found in the seventies (barring a few standouts like “Downeaster ‘Alexa’”). It’s impossible to imagine any other voice or piano touch on iconic tunes like “Scenes,” “Movin’ Out,” “Angry Young Man,” “New York State of Mind,” “Miami 2017,” and of course his eternal sugar-stick, “Piano Man.” Popular deep cuts like “Summer, Highland Falls,” “She’s Always a Woman,” and “Vienna” further showcased Joel’s rarely-acknowledged lyrical depth, a signature blend of bite and melancholy crafted with an Ira Gershwin-esque ear for the perfect rhyme. And so far from being outdated, lyrics like “Miami 2017” or “Goodnight Saigon” have only grown more haunting in the shadow of 9/11 and the Afghan War.

But Joel never chased political relevance. His peculiar iconoclasm manifested in not being political just at the moment when all his peers were. At a multi-artist event in seventies Cuba, he watched them walk out and deliver carefully prepped pro-communist speeches in Spanish, to minimal crowd response. When it was his turn, he shrugged and said, “No hablo español,” then launched his set. In an instant, kids were rushing the stage.

Granted, he had moments like the famous “keyboard flip” in glasnost-era Moscow, where the audience was lit up so police could remove any fans displaying an “excessive” response. But it was all about the music, even in Moscow. He once recalled another night on that tour where the press asked him political questions while he sat cross-legged and bored on the stage, finally cutting them off with, “Does anyone have a question about music?”

Joel maintains that compartmentalization to this day, a refreshing exception to the tendencies of some of his blue-state entertainment peers. In 2016, he commented that Donald Trump’s campaign was “very entertaining,” then told people not to read anything deep into that, because after all, “who cares about the political opinions of a piano player?” More recently, he’s chosen to give no comment whatsoever on the Gaza war, while other Jewish celebrities have vocally taken sides. This has no doubt frustrated many of his Jewish fans. It would certainly do no harm for him to signal support for Israel, and perhaps in a symbolic sense it could do some good. At the same time, if you understand Billy Joel, then you understand that making political statements of any kind, on any side, is just not who Billy Joel is. He’s the piano man. That’s all.

Unlike some contemporaries, Joel’s musical gifts extended beyond writing and performing to teaching, something I grew to appreciate as I became a teacher myself. Through the decades, he became known for “masterclasses” where he would take audience questions, share insider knowledge, and break down the writing process for fan favorites.

But perhaps his most memorable Q&A, from a 1996 appearance, has nothing to do with his own songs. It begins with a woman asking if he can compose a piece on the spot. He bluntly says “no” but offers to play a piece of music that inspires him—Samuel Barber’s “Adagio for Strings.” Then, while playing it roughly on synths, he relates an epiphany he had while hearing the piece on the radio in a rainy-day traffic jam. “It was around Easter time,” he recalls, “which is one of those ‘holy' times of year, you know?” As the music built up to its peak, something came over him that he couldn’t describe or explain. Then, at the climax, the sun shot out of the clouds, and the traffic cleared, but Joel had to pull over, because he was “bawling [his] eyes out.” “I lost control. I just lost it. What happened?”

What happened, he says, is that he realized “This is what I love about music. This is what I want to do. This is what I want to create. It’s what I’ve always tried to create. . . And I hope before I can’t write anymore, I can create music like that.”

Perhaps this is what Chuck Klosterman meant. But perhaps there are worse things than trying too hard. Whatever else can be said of Billy Joel, it will never be said that he didn’t try.

I love Billy Joel. There, I said it.

The most accurate Billy Joel moment was when a fan asked him who “She’s Got a Way” was written for. He thinks about it for a full 20 seconds, before replying: “I think it was about… uh… about the first woman that I married” https://youtu.be/WFfmkj9BzkA?si=FNF46DseHyn_aO88