God Raised a Body

Why the physical resurrection matters

Happy Easter! Or, as I grew up saying, “Alleluia, he is risen!” to which you were expected to reply, “He is risen indeed, alleluia!”

Today, my social media was full of Christian friends and acquaintances honoring this high Holy Day as it’s meant to be honored. Families dressed up, baptisms and confirmations were celebrated, favorite pieces of poetry and music were exchanged. All of us coming together with our loved ones to celebrate hope and faith in renewal.

Or sorry, not quite. I was looking at the Vice President’s Twitter, not to be confused with something that represents normal Americans, who are today (as ever) not quite sure what Kamala’s on about. But she certainly sounded much more passionate when tweeting about the Transgender Day of Visibility, which happened to fall on Easter Sunday this year. As someone astutely put it, you can tell which of the two religions has Kamala’s heart.

Much has been made of the clash, which wasn’t exactly planned (March 31 has been a designated LGBTQ+ Holy Day since 2009) but still illustrates rather obviously the repaganizing of the calendar. The Easter bunny on the White House letterhead added a nice surreal touch. Of course, fact-checkers leapt into action to remind everyone that Trans Day of Visibility has a long and storied history of presidential proclamations in its honor, dating all the way back to [checks notes] 2021. A clever friend of mine hopes for the funniest outcome of all this, which would be the transformation of all these new March and April Holy Days into movable feasts relative to the Paschal season/Passover, thus igniting the movement’s very own quartodeciman controversy.

Seriously, it is funny, and it deserves every bit of the ridicule it got today, as do the various nauseating posts from progressive “Christians” who are smugly explaining why ACK-shully, you can celebrate both days at the same time! Indeed, as one “queer theology” account informs us, this coincidence is “holy and serendipitous.” So far from being in conflict with one another, “these two observances enlighten, enrich, and elucidate each other.” Trans people are innocent victims of state power, just like Jesus. Trans people must “rise up” against the forces of death, just like Jesus.

It sounds inspiring. Of course, it’s all lies. A facade of lies, built on a pile of bones. As Prisha Mosley commented wryly, “Happy #TransDayOfVisibility! Never forget—if you’re visible today, the same eyes celebrating you now might look at you with disdain later on.”

I met Prisha last month outside a Planned Parenthood in Lansing. As you can read about here, the day didn’t go as hoped, but it proved very revealing. I appreciated the opportunity to get to know Prisha better, even though I knew the outlines of her detransition story already. Meeting her in person made it vivid. She certainly encountered a lot of disdain from the counter-protesters who had arrived early to drown her out. For their part, they insisted they were very happy. Whether they were protesting too much is left as an exercise for the reader.

Around the same time, Prisha announced that she was pregnant, something she hadn’t been sure was possible. But she’s not the only detransitioned woman to experience fertility. Daisy Strongin, a former trans vlogger who’s become a Catholic wife and mother, recently gave birth to her second child. But even this great joy was overshadowed by great sorrow, as she vulnerably chose to share in a picture of herself crying and bottle-feeding the baby. “These are not happy tears,” she wrote. They were tears of pain for what she couldn’t do, for what had been taken from her.

Men who have been similarly damaged by “trans care” have less of a public presence, but some of them have shared their stories too. In a documentary I reviewed recently, two of them recall the harrowing experience of having their genitals amputated. It’s a trauma they must now carry every day, just as women like Prisha and Daisy must carry the trauma of losing their breasts.

As I consider these unspeakably painful stories this Easter, I feel with a special urgency the power and necessity of Jesus Christ’s bodily resurrection. Too many theologians, too clever by half, have tried to “spiritualize” this doctrine. They patiently explain to the rest of us that of course Jesus couldn’t have had a body. Do we seriously think the risen Jesus had functioning organs? Did he have kidneys? Did he digest and pass food?

These questions are sometimes tossed out rhetorically, as if they answer themselves, before the enlightened Scholar moves on to his next point. Dale Allison prefers to imagine a “spiritual resurrection,” in which Jesus appeared to the disciples as a ghostly apparition, though still (Allison assures us) definitely not “a defeated victim of death.” Casper Invictus, as it were.

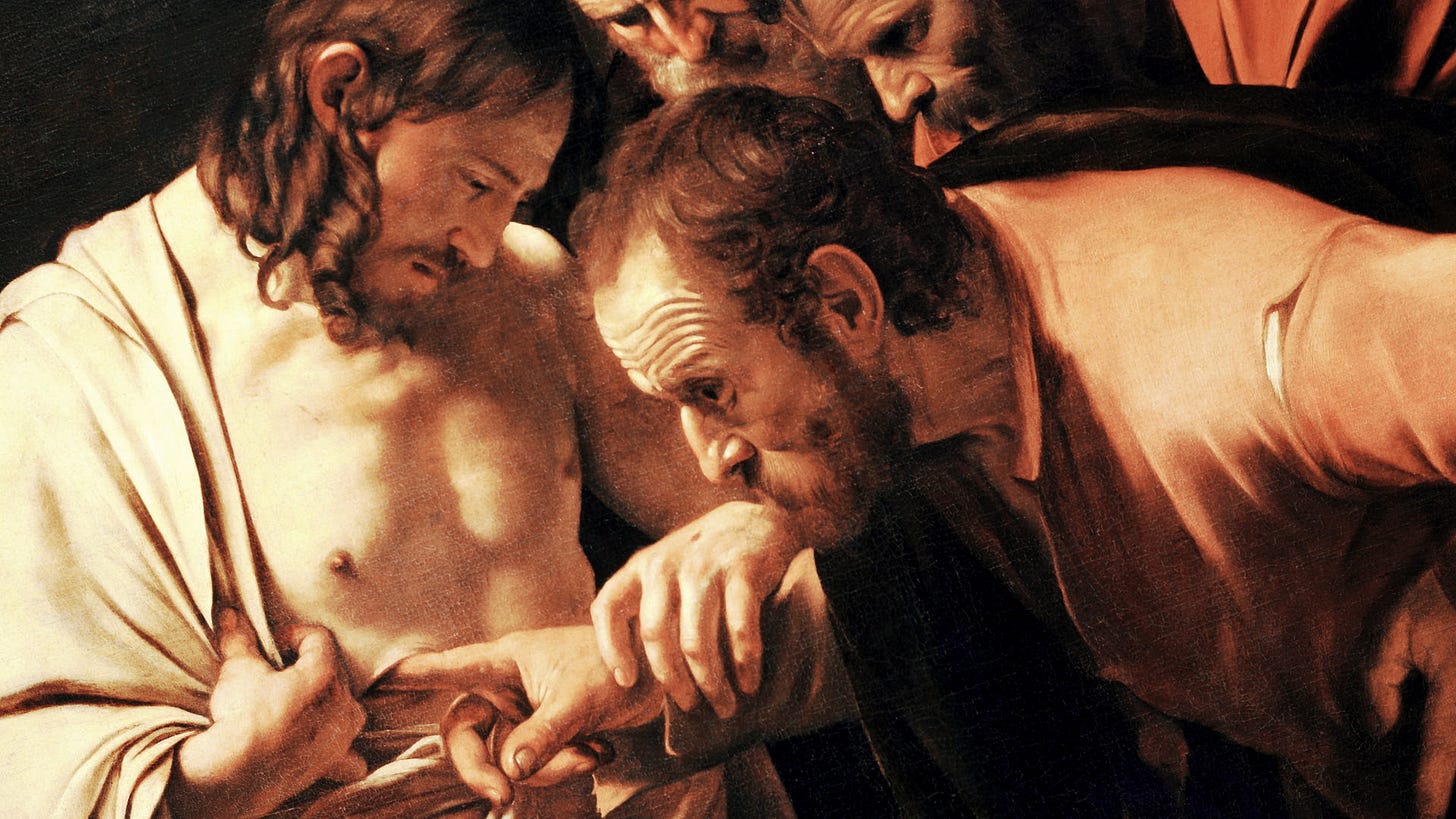

I believe the gospels don’t leave that option open to us, nor did they intend to. The risen Jesus who steps out of their pages certainly didn’t seem to intend to. True, his body has taken on new powers it didn’t have before, but he still invites the disciples to test its solid reality—most famously, Doubting Thomas, with his finger in the spear-scar. Thomas refuses to believe until he receives this most tangible proof, then falls to his knees before his Lord and God.

What do these lingering scars mean? To the Christian, they bear witness to that undeniable physicality of Jesus’ resurrection, which simultaneously destroys death and makes sure we will not forget how it was destroyed.

But there’s a dark undercurrent in trans subculture which seeks to twist and coopt such iconic images of Christ’s body, both crucified and resurrected. Prisha includes some in a thread full of “religious” trans art here. There’s even an image of Doubting Thomas putting a finger in a mastectomy scar. This reimagining of Christ’s wounds is a recurring motif. These pieces are gruesome to look at for Christians, but they’re eye-opening. They can be read as blasphemy, which is legitimate. They certainly are blasphemous. But we must bear in mind that to whatever degree the artists intend to represent their own life stories, such images are also a product of deeply buried trauma. In some cases, this art may also represent an attempt to reject a past in the Christian church. Unable to forget Jesus altogether, the artists attempt to remake him in their image.

But Jesus can’t be remade. He can’t be coopted. He offers himself to us as he is, not as people would like him to be. He offers the words of hope they need to hear, not the words of affirmation they want to hear. The young person who has irreversibly harmed himself seeks to be told that he didn’t make a mistake, that nothing is broken, that all is well. He seeks this even as he knows, deep down, that it is a lie.

Easter hope is not the reassurance that all is well. It is not the pretense that things which have been broken were never broken in the first place. It is the promise that what was broken can be mended. It is the assurance that though all is not well, all will be well.

In comments on young Daisy’s pictures of herself crying with her newborn, many women offered encouragement, but in addition to this, some assured her that she was right to weep. Tears of sadness and anger were right in that moment, as Daisy recognized her brokenness all over again. But as a Christian, she has been offered the one thing that can bring healing, the one truth that will outlast every lie: that her Redeemer liveth, and that in her flesh, she shall see God.

What form will that flesh take? Today I was reminded of John Donne’s captivating sermon on the resurrection of the body, considering what this mysterious doctrine means for us. How will this be for us who are not Jesus, some of whom have lost pieces of ourselves along life’s way? Donne answers, unforgettably:

Where be all the splinters of that bone, which a shot hath shivered and scattered in the air? Where be all the atoms of that flesh, which a corrosive hath eat away, or a consumption hath breathed, and exhaled away from our arms, and other limbs? In what wrinkle, in what furrow, in what bowel of the earth, lie all the grains of the ashes of a body burnt a thousand years since? In what corner, in what ventricle of the sea, lies all the jelly of a body drowned in the general flood? What coherence, what sympathy, what dependence maintains any relation, any correspondence, between that arm which was lost in Europe, and that leg, that was lost in Africa or Asia, scores of years between? One humour of our dead body produces worms, and those worms suck and exhaust all other humour, and then all dies, and all dries, and molders into dust, and that dust is blown into the river, and that puddled water tumbled into the sea, and that ebbs and flows in infinite revolutions, and still, still God knows in what cabinet every seed-pearl lies, in what part of the world every grain of every man’s dust lies; and sibilat populum suum (as his prophet speaks in another case), he whispers, he hisses, he beckons for the bodies of his saints, and in the twinkling of an eye, that body that was scattered over all the elements, is sat down at the right hand of God, in a glorious resurrection. A dropsy hath extended me to an enormous corpulency, and unwieldiness; a consumption hath attenuated me to a feeble macilency and leanness, and God raises me a body, such as it should have been, if these infirmities had not intervened and deformed it.

“God raises me a body, such as it should have been.” Such is our Easter triumph. Such is our Easter joy. Such is our Easter hope.

Christus resurrexit, sicut dixit. Christ has risen, as he said. Alleluia.

Amen.

I've never had a problem with believers who cremate. Because all matter belongs to God and if he can make man out of the dust of the ground, certainly he can remake man out of his own ashes. The John Donne sermon reconvinced me that being anti-cremation as a point of Christian theology necessarily calls into question one's faith in God's power to resurrect and renew the human body.

Allelulia!!!