Hero With a Thousand Enemies

On Watership Down

Recently, I had the pleasure of being invited back to National Review’s Great Books podcast, talking about Richard Adams’ classic Watership Down. You can listen here, and if curious you can also listen here to my previous appearance, discussing Robert Bolt’s A Man for All Seasons. The episodes are packed very tightly, and we can only cover so much, but John Miller is an excellent host. Last time, I gave paid subscribers an exclusive deeper dive into my thoughts on the work, so I’ll do the same here after a little preview for free readers. As always, if you’re already supporting my writing, thank you so much, and if not, an annual subscription is only $40 a year (or you can try a month for $5). This Stack is currently my most reliable income stream, so you are literally paying my bills.

Watership Down was one of the most formative novels of my childhood. But Richard Adams never intended it to be a “children’s novel” per se, even though he wrote it for his daughters. He explains in his introduction that it all began when they demanded a story on a long car ride. “Alright,” he complied, “Once upon a time, there were two rabbits named…er…Hazel and Fiver…” It took a protracted period of nagging from the girls to make Daddy put the whole story between covers. One night, he says he was reading aloud from “a not-very-good book,” then threw it across the room and exclaimed, “Good Lord, I could write better than that myself!” To which one of the girls replied, “Well I only wish you would Daddy, instead of keeping on talking about it.”

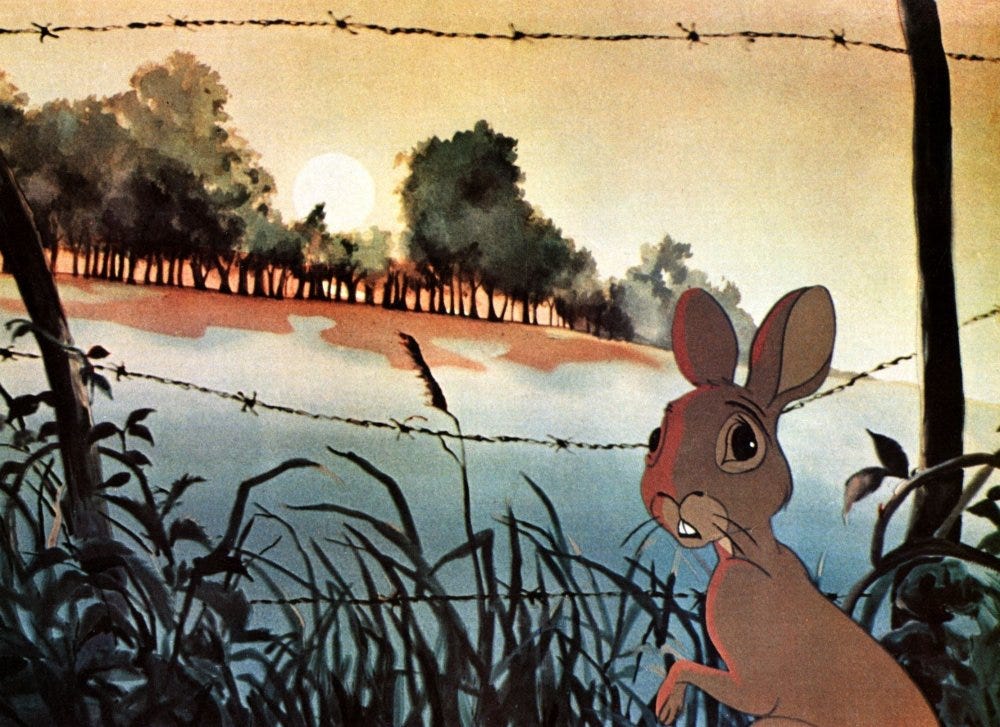

Adams didn’t particularly believe in children’s books as such, in the sense that he didn’t believe in imposing too many prescriptive boundaries on what children read. In his own words, “I’ve always said that Watership Down is not a book for children. I say: it’s a book, and anyone who wants to read it can read it.” The film adaptation is famously dark, with multiple reviews from people who will cheerfully tell you how it traumatized them as children. But the film is a pale imitation of the novel, where the contrast between whimsy and violence feels less jarring. Still, the manuscript initially racked up no fewer than seven rejections from publishers who thought it fell between stools. It finally found a home with one-man London publisher Rex Collings, who wrote to an associate, “I’ve just taken on a novel about rabbits, one of them with extra-sensory perception. Do you think I’m mad?”

The first edition received rave reviews from London critics. I still remember the wonderfully overdramatic blurb on the back of our old paperback, from the London Times: “I announce, with trembling pleasure, the appearance of a great story.” Reviews like this caught the ear of Macmillan USA across the pond, which published the first American edition in 1974. It would go on to sell over a million copies worldwide. But not every critic was as thrilled as the London Times. There’s a delightful irony in the fact that National Review hosted my podcast discussion, considering how the magazine initially received the novel. Critic D. Keith Mano titled his review “Banal Bunnies” and reported that the book was “pleasant enough, but had about the same intellectual firepower as Dumbo.” It was “an adventure story, no more than that: rather a swashbuckling crude one to boot.” If you wanted to call it an “allegory,” you might as well call Bonanza an allegory.

This review probably made Adams laugh, and he might or might not have had it in mind when he stressed that he never intended the story to be “some sort of allegory or parable.” It really just was “the story about rabbits made up and told in the car.” Still, the story is, in the best sense, mythic.