Jesus Loves You

And Matthew Parris too

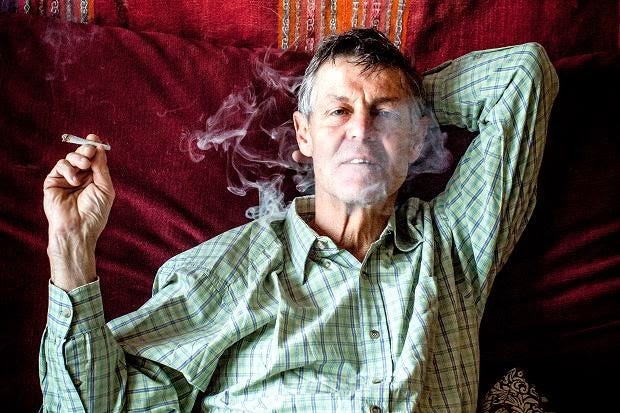

I’d forgotten how good Matthew Parris was. Scrolling through Spectator archives today, I rediscovered one of his finest moments, a deliciously savage evisceration of the Irish Catholic bishops’ reaction to the 2015 referendum on gay marriage. It passed with 62% of the vote. The statement from the Archbishop of Dublin was so hopelessly tepid that Parris, himself gay, couldn’t resist a little satirical paraphrase à la Exodus 32:

And it came to pass, as soon as he came nigh unto the camp, that he saw the Irish referendum’s huge majority for gay marriage, and the dancing: and Moses’ alarm was palpable…

And he took a copy of the Pink Paper and, flourishing it, said, ‘We have to stop and have a reality check, not move into denial of the realities.

‘I appreciate how these naked revellers feel on this day. That they feel this is something that is enriching the way they live. I think it is a social revolution.

‘We need to find a new language to connect with a whole generation of young people,’ the prophet concluded; then, casting off his garments, Moses said, ‘Hey, lead me to the coolest gay bar in the camp.’

Lest he be misunderstood, Parris is hardly rushing to take up the cause of the “emotional…ranting evangelicals,” whom he coolly regards as “rather dim.” And he’s hardly complaining about the success of the referendum. He was there on the ground floor of the whole gay marriage thing after all, plotting away in the Heaven nightclub with a young Ian McKellen and friends.

But that’s not the point. The point is that he can’t find anyone of any intellectual stature left in the English or the Roman church who will bother to argue with him. And that bothers him. He pines over the loss of a particular brand of conservative old Anglican—those literate, understated men of the cloth who could give you a Look over their bifocals and take your moral relativism down a peg. Almost, this sort of man persuaded a much younger Matthew to become a Christian. Now he is an old, settled atheist, and he can only sigh. “Silly me,” he concludes. “And there I was thinking they meant it.” There he’d gone again, thinking the church was really serious about things like theology and morality and objective absolutes that don’t lose their objective absoluteness just because 62% of a voting public disagrees. Where have you gone, Joseph Butler? A nation turns its lonely eyes to you.

But fond as he still is of Butler, Parris doesn’t think the old divine quite holds up. He prefers Hume in the final analysis. And over even Hume, he prefers Nietzsche, with his “eternal indictment” that he resolves to “write on walls, wherever there are walls.” In the same spirit, Parris once encouraged his fellow atheists to “shout their doubt out loud.” Though he hated to get into little scraps with “nice Anglicans and thoughtful Catholics” along the way, that wasn’t the real fight. It wasn’t those sorts of Christians he was worried about. Not the “best” Christians, who lack all conviction, but the worst, the evangelicals, who are full of passionate intensity because they actually believe something. It is against them that “we who do not believe must be ready with our paintbrushes, our chisels and our cans of aerosol spray.”

That was long ago, in 2007. Now Parris finds himself with a full can of aerosol and nothing to paint over. Like Richard the soapbox atheist in Graham Greene’s The End of the Affair, he was ready to jump up and make his case, except that nobody was listening.

Greene was writing in 1951. Parris was born in 1949. His grandmother was born in 1888. He still remembers that day in her last months when he was giving her his arm up a beach ramp. He was nineteen then, crass and cock-sure and quite certain he was the first out and proud heathen in the Parris lineage. But he wasn’t going to take potshots at what he assumed dear old Gram still believed about that sort of thing. He was an arsehole, but not that big of an arsehole. “Never mind, Grandma,” he said lightly as she limped along up the ramp, out of breath. “In the next life, you’ll be leaping around like a spring lamb!” He would never forget the moment she stopped, fixed him with a cold stare, and said, “You don’t think I’ve ever believed any of that nonsense, do you?”

So, all things considered, Parris is probably more surprised than anyone that a particular bit of his last Tuesday Times column has been taking off in Christian outlets everywhere this week. It’s tucked away at the end, after other bits and bites of gossip about Boris Johnson’s Worst Summer Ever, Who Pincher Pinched in the Carlton Club, etc. (Chris Pincher is the MP who reportedly groped two men while in his cups, thus triggering the government crisis that has led to Johnson’s resignation. Parris has written sympathetically about Pincher as a man caught out of time, not realizing this isn’t the 80s anymore.)

But scroll past all the chatter, and there is a simple, unexpected new section heading: “Jesus loves me.”

In a few short paragraphs, Parris sketches an encounter he had while walking home late from a recent speaking engagement. (By chance, just next door to the Carlton Club.) It was near midnight, late enough that the streets were deserted as he wound his way through London—six miles on foot, but pleasant exercise for Parris, a lean veteran of many marathons. His swimming game is less hot, though he did have fifteen minutes of fame back in ‘78 when he jumped in the freezing Thames to rescue a dog for two children. Maggie Thatcher had been all graceful smiles when she gave him an RSPCA medal, but privately she told him that was stupid, it was only a dog. And so it was, but it made a great story at parties (especially the bit where the dog started humping Thatcher’s leg).

He stopped at a complicated intersection. As he waited, a scruffy young cyclist on a Deliveroo bike pedaled up next to him. With no introduction, the young man said, “You’re Matthew Parris.”

For U.S. readers, Deliveroo is a British online food delivery company. Parris estimates that it would take 70-some hours for this young man to make what he had just made for a single night of speaking.

When he acknowledged he’d been pegged, the cyclist asked him a question, with equal forthrightness: “Do you believe in the Lord Jesus?”

To this, Matthew gave the answer his readers would expect him to give. He said that he believes Jesus existed, certainly. Certainly, Jesus was a great man, a wonderful teacher. It warms Matthew’s heart to hear Prince Charles refer to “Our Lord Jesus Christ” on the radio. Matthew sings hymns. Matthew delights in the King James. He is hushed by cathedrals. He has said he says his prayers every night, “not because anyone is listening, but because I always have.” He gets misty-eyed at the inscription on a particular gravestone in a cemetery he’s visited, for an infant who died: “Touch’d the Earth and gone to Glory.”

Except he doesn’t really think there is such a thing as Glory. Because, as he told the Deliveroo cyclist, in the end, he doesn’t think Jesus was the son of God. He doesn’t even believe in God.

“But He said He was,” the cyclist pushed back.

Well, Matthew said, then that poor brave great wise man was under a delusion about his paternity.

After considering this conjecture a moment, the young man said, “Well, Jesus loves you, even if you won’t acknowledge him. I will pray for you.” Then he cycled away and left Matthew to walk home alone, “curiously moved.”

Others have been less so. On Facebook, Stephen Law says that it’s a very effective marketing strategy, this. A kind of inept love bombing, one could say. Observed in cults. Not that they’re cynical, necessarily. They think they’re just spreading the love. A known pattern. Law might as well be narrating a nature documentary: “Here, we see the evangelical Deliveroo cyclist in his natural habitat…”

Parris thinks a lot about what it means to be moved. Once, he felt it when he heard someone playing the tinny old Yamaha chained up by the lift at London’s St. Pancras station. He was hurrying for the sake of hurrying, thinking about his next column, in a state about the state of the state. Then the piano broke in, and he stopped. A young African man was making the music. It was romantic, yet triumphant. It was “all surging chords and soaring crescendoes.” He listened, took a clip on his phone as a keepsake. He got the man’s name—Ashley—and the name of the piece, but he would forget that. Then he walked on and up the escalator, the music falling away behind him. Tears pricked his eyes. He was moved, he wrote later. But what did that mean?

There exists a feeling for whose precise description I know no word or phrase in the English language. Yet we must all have experienced this, sometimes powerfully. ‘Moved’ comes the closest but doesn’t quite do it. One is moved to… what? Tears of sorrow, joy, regret… but moved always to something. One is moved by… what? Beauty, longing, hope, compassion… but always moved by something. The word ‘moved’ tends to anticipate elaboration, explanation of the what, how or why. Unsupported, it stands awkwardly, asking for something proximate.

But I was just moved. I said tears pricked my eyes, and so they did, but I was neither sad nor happy, pleased nor sorry. Feeling moved did not relate to anything or anyone in the world. I felt, yes, connected to something, and the music had touched me, made the connection, but a connection, I think, to something within. All I know is that it made the things preoccupying me seem small, less important, temporary; while what engulfed me felt timeless, overarching, like the stars at night.

The moment had passed soon. The state was still in a state, and he still had a column to write. But he couldn’t shake “the sense of having been momentarily lifted: from what, I know very well; to what, I know not at all. But lifted.”

It was like that now, that silent night. The state was in a state, again. There would be a column to write, again. But again, he had found himself walking home, moved.

Parris is a Last of the Breed. This story stirs up sympathy for a man who is no longer with the culture, which has progressed to inanity. Sadly, were he to be converted, the environment wouldn't likely change much - "Those literate, understated men of the cloth who could give you a Look over their bifocals and take your moral relativism down a peg." are largely missing.