Jordan Peterson's Problem

Is the world made of matter, or is it made of what matters?

I should not be writing a Substack right now. I should be writing a chapter for (yet another) anthology of essays on Jordan Peterson. Naturally, there’s only one way to resolve this problem: Write a Substack on Jordan Peterson. Not a terribly long Substack, though. I need to save full polished thoughts for the book you’ll be expected to buy when it comes out. This is just part of my process, you understand.

While gathering notes for this chapter, I’ve been revisiting Peterson’s old debate clash with Sam Harris in the summer of 2018. As I’ve written elsewhere, it was my analysis of this clash that brought me into the Discourse as a commentator on the whole Peterson phenomenon, and so from there as a commentator on Things in General. (Fortunately, I’ve found enough other interesting things to write about as Peterson’s wave has crashed and receded that my own platform, while small, has grown.)

There are many possible lenses through which to view the Peterson-Harris debates in hindsight. They were rather endearingly disorganized rounds of philosophical, religious and political brawling, from which both combatants in my estimation emerged rather bloodied. Not that they weren’t good-faith interlocutors, each seeking sincerely to understand the other (aided valiantly by moderators Bret Weinstein and Douglas Murray as roadblocks presented themselves). They just seemed consistently to be on different wavelengths.

This was partly a matter of style and personality. Peterson is naturally intuitive, while Harris is naturally analytical. Peterson is the archetypal rambling professor, while Harris cuts to the chase. Peterson loves to wander through the garden of ideas and smell the roses, while Harris is constantly checking his watch.

The confusion was also a function of Harris’s frustration in trying to pin down who and what exactly Peterson was, qua religious and philosophical opponent. If Peterson wasn’t a Christian apologist, then what was his angle? What was his game?

Peterson tried to explain his angle several times over the course of the four nights: It was, he wanted to hope, not so far removed from Harris’s angle. As he quoted back to Harris from The Moral Landscape, Harris wanted to salvage psychological truths from “the rubble” of the world’s religions. “Well,” Peterson said, “I’m trying to find the important psychological truths in the rubble. But we also have to decide if we agree about that. So, are there important psychological truths to be found in the rubble?”

Peterson wants to answer this question with another question. His problem, which he believes is everyone’s problem, can be boiled down to this: Is the world made up of matter, or is it made up of what matters? Is it a collection of objects, or a forum for action?

If atoms are the fundamental building blocks of the world as we know it, then humanity should be able to complete its knowledge-gathering quest via the scientific method. This is the world of “objective fact.” But what if the material is not the most fundamental? What if the primary constitutive element of reality is immaterial, not discoverable by “objective” means (as the scientific method defines “objective” — this point is important)? This is the world of “subjective value,” and the scientific method will not be up to the task of unlocking it.

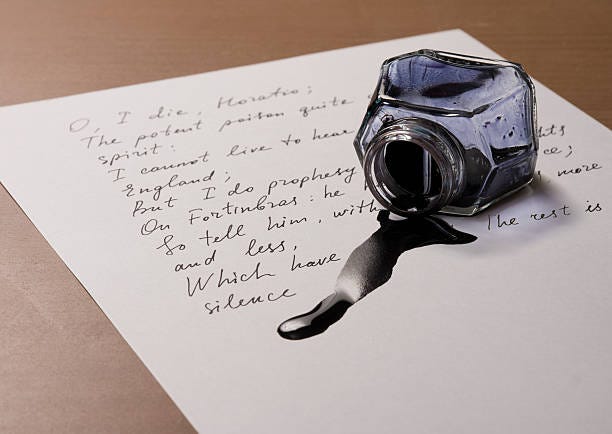

How, then, do we take the facts with which we are constantly bombarded and make ordered sense out of them? How do we make the move from “fact” to “value” which is fundamental to human existence itself? We need some interpretive grid, some mediating framework. This mediating framework, Peterson wants to propose, is Story. It is the abstract made concrete. It is “Logos,” Word, made flesh. And this has been nowhere better expressed than in the stories of the Bible. Thus, Peterson’s challenge to Harris is not just that we shouldn’t unhitch ourselves from the stories of the Bible. It’s that we can’t.

Peterson distilled this perhaps most clearly in one of his old papers, “A psycho-ontological analysis of Genesis.” This is a key passage:

Cain and Abel emerge as the hostile brothers—archetypal responses to this new and self-conscious existence. One brother, Abel, provides an early model for the redemptive savior, as a genuine and voluntary incarnation of Logos. The other, Cain, refuses his responsibility, justifies that refusal with his existential pain and fear, and turns savage, destructive, corrupt and murderous. Thus, two pathways of morality are laid out as primary modes of ethical being, in a world composed of the interplay between chaos and order.

Are these modes real? It depends on what you mean by real. That, in turn, is a matter of axiomatic preference—faith, if you will (as has always been claimed). From a strictly scientific perspective, the question itself may not even be real. After all, a paradigm presumes the evidence that sustains it. If the world of experience is made of chaos and order, then the choice between the path of Cain and the path of Abel is the most important choice that anyone can ever make. If everything is merely material, by contrast, the choice does not even exist.

As I read and listen to Peterson, I constantly find myself thinking that he is so close, yet so far. He accepts the fact-value split as a given and agonizes over the best means by which to mediate between. But the question that demands to be asked is whether there are some values which are also facts.

All this is really circling around natural law — a trending topic, I gather (I’m not supposed to be on Twitter but I did catch something about white nationalism or something). Anyway, for those new to my work, you can read a little piece I wrote about this here at the Stack. I called it “What We Can’t Not Know,” thereby shamelessly ripping off the Catholic philosopher J. Budziszewski. That piece in turn begat a rather lively back-and-forth of my own with historian Tom Holland, who, like Peterson, also seems to want to insist that moral value exists in the realm of the “subjective.” But with all due respect to Holland, who’s probably reading this, I don’t think he really believes that, any more than I think Peterson really believes that. Peterson, after all, is hinting strongly that “everything is [NOT] merely material.” It should follow that the world is discoverably, objectively immaterial. Should it not?

Story enlightens. It sheds light. It makes us see, as Joseph Conrad tells us all good story-tellers should, by vocation, by obligation. It provides us a glimpse of that truth for which we have forgotten to ask. But this truth is not a song we have composed as we sang it. It is not a path we have made as we trod it. If all the world’s a stage, we are only players. And, in the words of C. S. Lewis, if Shakespeare and Hamlet could ever meet, it must be Shakespeare’s doing. Hamlet can initiate nothing.