N. T. Wright and The Inner Ring

On the hubris of the Protestant elite

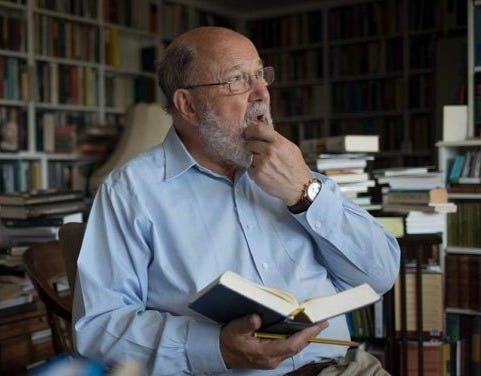

I have never been a great fan of N. T. Wright. I wasn’t shaped by his theological work and have looked elsewhere for robust scholarship on the resurrection. However, I’ve always been aware of him as a little “o” orthodox voice in Church of England spaces, one of the few clergymen willing to say he believed things about things. For decades, that distinction has given him considerable credibility with serious Protestants around the globe. A number of them point to him as instrumental in their own journeys to faith. When friends in turn come to them with questions about Christianity, Wright is a scholar they can pull off the shelf with a sense of security: Here, this guy is the real deal. You can take him to the bank. Also, his accent is really plummy and cool.

In other words, Wright is a Protestant elite—a phrase now rarely applied in the United States since the collapse of the mainline, but still apt in UK contexts.

There’s been some interesting recent writing about why conservative American Protestants in particular don’t have (and whether they need) elites. Is it the lack of an intellectual ecosystem? Is it a patronage problem? Is it an external or internal problem? Is it a problem at all?

There are many directions you could go in trying to answer these questions. Some lament the fact that the inherently fragmented nature of Protestantism has left our brightest and best without a support structure. There’s something to that lament. However, there’s also something to the argument that the fewer self-styled elites we have, the better, because identifying oneself as an elite makes you vulnerable to corruption and hubris. By way of example, I’m afraid I can’t think of a more perfect illustration than N. T. Wright.

Recently, a couple clips have been going viral from new episodes of the Ask N. T. Wright Anything podcast, hosted by Australian New Testament scholar Michael Bird. One in particular has drawn intense righteous outrage, an answer to a question from a German woman about abortion. The woman says she was raised Christian, and as part of her upbringing she was taught that abortion is murder. But now, as a student regularly confronted by pro-choice peers, she feels less confident. The pro-life position is no longer intuitive to her, especially in early stages of the pregnancy before the baby has taken on a recognizably baby-like shape. The idea that life begins and must be defended from the moment of conception feels “abstract.” And what about the “difficult ethical questions” that arise in cases like pregnancy from rape? She looks to Wright for help “to better understand the Christian reasoning on this issue.”

At this point, one would hope that an esteemed conservative biblical scholar and clergyman would have a clear, sound answer ready for this young woman. Instead, the former Bishop of Durham throat-cleared his way into an extended apology for selective child murder.

We have to be “very, very careful” about this “ethical hot potato,” you see, and careful not to just go and call it “murdering an unborn child.” Because in cases like rape, incest, “mental health” of the mother, or even cases where the child might be “deformed” in some way, there could be a “very, very strong argument” for doing just that. He tells a story about a pregnant family friend who was exposed to rubella and had a temporary scare about how this might have affected her unborn child. She was planning to abort until it mercifully turned out that the child was unharmed after all. However, for those children who aren’t so lucky, it might be that “with sorrow and a bit of shame, the best thing to do is as soon as possible to, to…um, terminate this pregnancy.” And “the sooner the better,” he goes on to add, because at a certain point the child will become “a viable human being” who should be “cherished.” Not that he’s “medically qualified” to know exactly where that point is. We leave such things to the philosopher doctors.

Amazingly, in the middle of all this Wright has the chutzpah to invoke ancient Roman infant exposure while emphasizing that Christians can’t support at-birth abortion. That’s still a bridge too far for the former bishop. However, if Christians are shouting too loudly at people about baby murder and such, especially if they’re men (or worse, celibate priests), then the “optics” are bad, and heaven forbid we have bad optics. So what Christians need to do, you see, is they need to inhabit a very specific Goldilocks zone: not too infanticidal, not too embarrassingly pro-life, but just Wright.

These remarks have provoked waves of shock and deep disillusionment among those serious younger Protestants who looked up to Wright, academically and spiritually. I can’t find any older comments quite this explicitly awful on the record from him. However, there were signs.

One particularly large red flag went up last fall, in an election season interview about politics and the gospel. Wright’s interviewer asked him to enlighten listeners about just why certain Christians are so involved in “culture wars.” Seriously, why are they like this? Well, Wright explained, that’s a huge topic, “a whole seminar in itself” really, but in a nutshell, it’s because no one’s ever taught them how to do political theology Wright. These poor, bumbling evangelical souls are crudely mashing up a confused political theology with a confused theology of the eschaton, you see. They’re so heavenly-minded, always thinking about the rapture and stuff, that they can’t figure out how to be of any earthly good, unless something triggers one of their knee-jerk insecurities—about sex, for example. That’s how the pro-life movement got started, by the by. It was really a “power play” by men who got the ick over women having lots of sex, but they tried to deflect by claiming it was about not wanting babies to killed. So they became “vitriolically” anti-abortion, which was hypocritical because they were also “vitriolically” pro-gun. And so now everything is horribly “simplistic” and “polarized,” and no one understands how to “talk about this sensibly.” If only they would just buy Wright’s latest book.

In fact, an online friend of mine did buy that book, co-written with the aforementioned Michael Bird, who also makes a regular habit of sneering at right-wing American Christians. As this new viral clip of Wright was going around, my friend sent me a sample and reflected on how empty it was of actual substance—all fluff and vague handwaving about “nuance,” no real guidance on real issues.

However, when Wright has found his thundering political voice, it has reliably not been on behalf of those issues where the Christian position is most obvious. Go back further to this interview with a Catholic newspaper from 2004, and you’ll find him in fact becoming angry when the reporter suggests that abortion is the defining moral issue of our time. Wright rejects this proposal and claims that our defining moral issue is actually the global debt, which we could solve with a few neat tricks if only all the greedy rich people would cooperate. Why are we even discussing abortion, he asks, when there are children “whose economic circumstances are such that it would almost be better if they hadn’t been born”?

How exactly this man became a go-to expert on American political theology, I’m not quite sure. But I think it’s become convenient for some American Protestants to call on him as they search for sticks with which to beat other American Protestants to their political right. You could reliably find Wright in the same sorts of spaces hosting, say, Francis Collins—another left-wing Protestant elite. And sometimes, as during COVID, you could find them collaborating on the same condescending lecture about masks, vaccines, church closures, and such. That particular collaboration was hosted by Biologos, an organization founded by Collins that built its brand on complaining about “anti-science” evangelicals.

Sociologically, these things are all of a piece. The types of Protestants who tend to oppose abortion most loudly have been the types of Protestants who are generally most suspicious of establishment narratives, political and academic. Accordingly, the types of Protestants who look down on them are those who seek establishment credibility. In the rearview mirror, movements like the Religious Right appear intensely embarrassing to them. In order to be politically or academically respectable, they all have to agree that whatever “cultural engagement” is supposed to look like for a Christian, of course it won’t look like how those people did it.

You can hear this exasperated tone in Christian Smith’s new book Why Religion Went Obsolete, a work pitching itself as impartial sociology. But Smith just can’t keep the sneer out of his voice when it comes time to talk about the rise of the Moral Majority, which he pegs as “one of the crucial disturbances” in the culture that eventually made religion obsolete. He traces its roots back to the modernist-fundamentalist wars of the 20s, after which both neo-evangelicals and fundamentalists sought to influence the culture in distinct ways. Post-war figures like Carl F. H. Henry and Billy Graham pursued a hopeful project of “gospel-centered” missiology, pragmatically cooperating with the mainline as needed, while fundamentalists slowly grew an independent mass media audience first through radio, then televangelism. Unlike once-privileged mainline Protestant productions, which ironically lost their market share when networks retired free public service programming, fundamentalists learned to fight for a niche that would become an empire.

Smith identifies the 70s as the moment when evangelicalism gave way to “mission drift,” trading the spirit of evangelism for the spirit of politics. His main culprit is the Reformed Presbyterian evangelist Francis Schaeffer, whose early legacy of writing and community hospitality in the Swiss Alps embodied the sort of winsome cultural engagement Smith prefers. But Schaeffer justified his political pivot as a necessary response to an encroaching culture of death and sexual decadence. He believed Christians could not afford to remain quietly ensconced in mountain enclaves, but were compelled to fight fire with fire, and if God so willed, to “change the course of history by returning to biblical Truth.” His book How Then Shall We Live would go on to become a rallying cry for the Religious Right.

With their strident ‘Christ against culture’ posture, Smith judges, the Religious Right undid the neo-evangelicals’ thoughtful bridge-building work, and in its place “helped create a larger sociocultural-political dynamic of hostility, coercion, and polarization that only grew worse with time.” He believes Schaeffer’s manifestos against secular humanism only brought out old fundamentalist “insecurities,” fostered a cultural persecution complex, and replaced a message of welcome with a declaration of war.

No doubt to Smith, figures like Wright and Collins embody an ideal genteel Protestantism. But that genteel, collegial spirit extends only to Christians they perceive as social equals. When it comes to Christians who fall below them in social status by vocally proclaiming ideas that embarrass the elite, the mask slips. Caught on a hot mic during a COVID panel discussion, Collins put on a Southern accent to mock the vaccine-hesitant. This ugly gesture sprang from the same hubris as Wright’s ignorant potted history of the American pro-life movement. In their distinct ways, they were saying the same thing, taking shots at the same target. (It’s also worth mentioning that long before COVID, Christians were ringing warning bells about Collins on the life issue, as he aggressively pushed for embryonic stem cell research.)

That contempt trickles down to younger Christians who are chafing to be numbered among the elite themselves. I’ve seen it, particularly in Christians who come out of (and want to leave behind) a more evangelical or fundamentalist background. They look to a Collins or a Wright as aspirational goals: men with credentials, success, and status in “the real world,” beyond the silos.

What I would want to tell these younger Christians is that there’s nothing wrong with seeking good credentials, pursuing excellence, or earning respect from unchurched peers. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to be good, period, not just “good for a Christian.”

But if you seek respect, let it be for your work’s sake, and not for the sake of joining The Inner Ring. This is C. S. Lewis’s warning in his essay by that name:

Over a drink, or a cup of coffee, disguised as triviality and sandwiched between two jokes, from the lips of a man, or woman, whom you have recently been getting to know rather better and whom you hope to know better still—just at the moment when you are most anxious not to appear crude, or naïf or a prig—the hint will come. It will be the hint of something which the public, the ignorant, romantic public, would never understand: something which even the outsiders in your own profession are apt to make a fuss about: but something, says your new friend, which “we”—and at the word “we” you try not to blush for mere pleasure—something “we always do.”

And you will be drawn in, if you are drawn in, not by desire for gain or ease, but simply because at that moment, when the cup was so near your lips, you cannot bear to be thrust back again into the cold outer world. It would be so terrible to see the other man’s face—that genial, confidential, delightfully sophisticated face—turn suddenly cold and contemptuous, to know that you had been tried for the Inner Ring and rejected.

In a different interview, Wright has said that the church “ought to be constantly in the business of reminding people how to do moral discourse.” I couldn’t agree more. Perhaps now that people have seen that genial face turn cold when speaking of God’s most vulnerable children, they will seek that moral instruction elsewhere. Be it so.

I think the quest for respectability is one of the easiest traps to fall into and has some of the worst consequences for one's soul in matters of religion. That doesn't mean that all ideas are equally valid, but the Christian faith and its moral implications are always scandalous in some way or another to every society.

For the record, this sort of thing is very much a trap I have fallen into myself and could easily in the future but for the grace of God, so I'm not throwing stones without pitching back at me.

World-class article and much needed context on Wright, but my absolute favorite part was the amazing puns on "Wright" :D