Never Again

A walk through the Holocaust Memorial Museum

I visited Washington, D.C. for the first time this month. After finishing my business there, I had a day free and wasn’t exactly sure how I was going to spend it. I had a vague idea of wandering around the National Mall and perhaps bumping into a friend who works on Capitol Hill. But after a bit of googling, my plans crystallized: Of course, I had to visit the Holocaust Memorial Museum.

To get in to see the Permanent Exhibit, you have to reserve a ticket, but it was a quiet weekday and this wasn’t difficult. After a leisurely morning, then afternoon coffee with a reader, I caught an Uber to go claim my slot. I noted the address: 100 Raoul Wallenberg Place. Wallenberg was one of the great heroes of the Holocaust, a Swedish Schindler who forged passports for numerous Jews to escape. In a bitterly tragic twist, he disappeared and is believed to have ended his own days in a Soviet prison after being detained on suspicion of espionage.

The museum puts its visitors through a security screening, which of course isn’t unique to them. Still, I can’t help wondering if they’ve been on higher alert than usual over the past few months, if they’ve received an uptick in threats.

After your screening, you are greeted by a young woman who hands you a small, crisp pamphlet, about the size of a passport. This is your “identification card,” telling the story of one Holocaust victim. I tuck mine away in my purse to read later. The young woman says a few more words to me and a few other visitors before the elevator carries us up, reminding us to be quiet and bear in mind that people come here to remember their families. In the elevator, there’s a small TV playing prison camp liberation footage on a loop, as the voice of an American soldier narrates what he’s seen. Many exhibits are accompanied by similar loops as you walk through.

Before you get to the Final Solution, you are taken through the rise of the Third Reich. There’s footage looping of an apoplectic Hitler, anti-Semitic posters, photos chronicling the progressively intensifying segregation. One photo shows a young man sitting on a park bench labeled “For Aryans only.” A page from a Nazi tabloid explains that because Jews are “born criminals,” they can’t smile, only twist their faces in “a devilish grin.”

On the Jewish day of atonement, 1938, this prayer was read aloud in synagogues throughout Germany, written by Berlin’s chief rabbi, Leo Baeck:

Our history is the history of the grandeur of the human soul and the dignity of human life. In this day of sorrow and pain, surrounded by infamy and shame, we will turn our eyes to the days of old. From generation to generation God redeemed our fathers, and he will redeem us in the days to come. We bow our heads before God and remain upright and erect before man. We know our way and we see the road to our goal.

I’m reminded of Viktor Frankl’s reflection that his generation had come to know “man as he really is.” For “After all, man is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz; however, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright, with the Lord’s Prayer or the Shema Yisrael on his lips.”

Later, I read that Baeck survived his imprisonment in the Theresienstadt ghetto camp, delivering lectures from memory and acting as a pillar of strength for the other inmates. After liberation, he intervened to stop revenge killings of the guards. He accepted a transport to England only after ensuring the health and comfort of the sick.

After the Anschluss, Austrian Jews were attacked and forced to perform menial tasks, like scrubbing sidewalks. I take a picture of a small crowd defacing a home with the word “Yud” in thick, calligraphically precise letters.

Another wall educates me about the doomed Evian Conference, a half-assed initiative to organize the admission of Jewish refugees. A British newspaper cartoon about the conference shows an old man in a kippah, slumped under a four-way street sign with “Go” on every side. The four roads radiate out from him in the shape of a swastika, each ending in a sign saying “Stop.” Franklin Roosevelt organized the conference but took pains to deflect attention from the fact that America’s own quota was severely limited. One by one, the nations shrugged their shoulders. Australia explained that it “does not have a racial problem, and [is] not desirous of importing one.” The attendee from British Mandatory Palestine, one Golda Meir, was not allowed to speak or participate.

Another exhibit refreshes my memory about how not only Jewish but non-Jewish Poles were purged. Poles in general were considered racially inferior. Some were conscripted for mass labor, others mass executed. One picture shows priests and teachers of Bydgoszcz sitting on hard cobblestones as they await their fate. A soldier stands over one of them who has his eyes closed, preparing for death. A priest stands watching them in the middle of the frame, looking severe and resolute. In another picture, the captives are blindfolded by SS men, about to be shot near the village of Palmiry. On display with it is the tree stump that marked their mass grave.

From another exhibit, I learn that the method of gassing was first developed as part of the Nazis’ disability euthanasia program, Operation T4. I read Hitler’s signed authorization that these people “may, after a humane, most careful assessment of their condition, be granted a merciful death.”

From here I make my way to perhaps the most awe-inspiring exhibit in the museum: a tower filled with portraits from the shtetl of Eishishok, located in what is now Lithuania. The 3500-strong community had been planted almost 900 years before. In 1941, the SS came and began to round them up, 250 at a time, driving them to their own ancient cemetery. There they were forced to undress, then shot and buried in open pits.

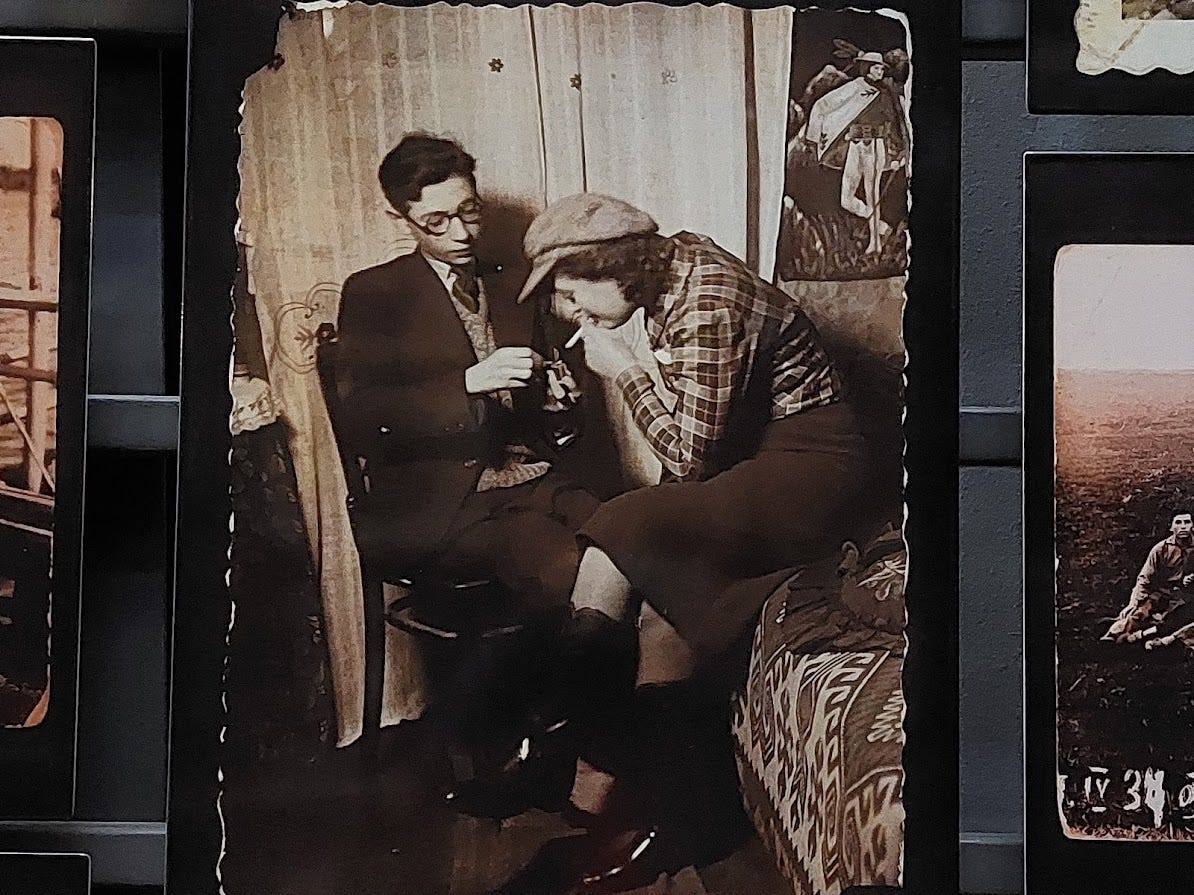

The family photographs in the tower span fifty years, some going back to the turn of the millennium. I crane my neck to look at the ascending mosaic, row on row of faces. I examine a few at eye level—here a group of students in a huddle, there a father with his little girl, there a young couple, the boy lighting the girl’s cigarette. She sits on the edge of a bed with her legs crossed, looking jaunty in stylish long boots and a cap. He looks serious in a suit and spectacles.

I’m now entering into the section dedicated to the ghettos and the camps. The slogan “ARBEIT MACHT FREI” has been reproduced in iron, the way it first appeared over the gates of Auschwitz and Dachau. I read about the Warsaw Uprising and the last days of political leader Szmul Zygielbojm, who escaped the ghetto to England and began a desperate awareness campaign. It was based on his intel that British media began releasing its first reports of death camps and gas chambers. After the uprising in May 1943, Zygielbojm received word that his second wife and stepson had been killed in the final liquidation. He then wrote a suicide letter, took poison, and died. He writes, “My comrades in the Warsaw ghetto fell with arms in their hands in the last heroic battle. I was not permitted to fall like them, together with them, but I belong with them, to their mass grave.”

I can’t remember if it started in the tower, or if it begins here, but at this point my knees have gone weak, shaking a little.

One display tells the story of a blue flowered felt belt picked up and worn by a teenage Auschwitz survivor. She hid it under her top and used it to cinch the sagging waistline of her striped prison uniform. She tried to convince her mother that she wasn’t getting thinner, the belt was just stretching. “Wearing this forbidden piece of finery was my pathetic act of defiance. I am still proud of it.”

Another display is dedicated to Chelmno, the first of the extermination camps. There’s a little pile of excavated objects in one place: a key, a knife, a thimble, buttons, a belt buckle. There are denture fragments. I can’t help thinking about those now in Israel who have been tasked with recovering what charred bits of the dead they can. I think about the worker who explained they couldn’t tell whether one skull belonged to a child or a young man, it had been so warped by fire.

There are stones here from the quarry of the Mauthausen camp, in Austria. Prisoners were forced to haul them up the 186 steps of the so-called “Staircase of Death,” then sometimes shoved off to tumble down and die.

An artist has created a sprawling mass death transport in miniature, showing crowds of men, women and children as they’re herded on the trains and into the gas chambers. I can’t take my eyes away from the tiny sculpted women and children, stripped naked and vulnerable just before they enter the “showers.” One mother gets down at eye level to soothe her child. And then, finally, they are all pressed together in a tortured mass of bodies, like figures in one of Gustav Doré’s woodcuts from Dante’s Inferno. One sign quotes a few words from an SS commandant: “I remember a woman who tried to throw her children out of the gas chamber, just as the door was closing. Weeping, she called out, ‘At least let my precious children live.’”

I nearly miss an exhibit dedicated to the victims of medical experiments. The footage on a loop has been hidden behind a wall with a warning, because it’s so graphic. I make myself watch some of it, but only some.

I spend some time in an exhibit called “Voices of the Holocaust” that plays a selection of survivor interviews, with a booklet of transcriptions so you can follow along. The voices are tough and calm. Their accents are beautiful. A couple of the men sound Jewish-American. One of them recalls the famously pointless task of carrying cement bags from one side of a compound to the other, back and forth, back and forth. Another recalls watching the weak prisoners fade and die, day by day. And the worst part was that you couldn’t cry. “You couldn’t cry in Auschwitz. You cried, you died, see?” But they tried to survive, and even to laugh. One remembers muttering imprecations under his breath in German, and when an officer would angrily turn around and ask, “Wat has du gesagt,” he would say, “Nothing.” It was his way of “getting even a little bit with them.” Another remembers how he used to go around the Blocks and sing, tell jokes, make people forget. But one woman admits that she couldn’t tell you everyone was strong, everyone was an angel. They were only human. She recalls how they would sometimes argue with each other, even steal from each other, mother from daughter, daughter from mother.

I pass by a window etched with names that mean nothing to me: Israel, Judita, Richard, Liszi, Pawel, Anna, Alma, Paula, Erwin, Eugen, Moric, Max, Zofia…

I reach the lower half of the shtetl tower exhibit I saw before. Here, there’s a tablet you can pick up that will tell you the story behind a photo if you point and aim. It then connects photo to related photo by a golden thread, if you want to keep exploring. I examine a photo of four young scholars whose paths diverged. Two of them escaped, and two did not. The one escaped to Palestine, the other to Argentina. There’s a similar photo of four young soccer players, wearing their team’s striped scarves. One left for America in the 20s. Another survived in the Soviet Union. A third was executed in the forest as a partisan. A fourth died in the shtetl massacre.

But almost more haunting to me are the photos where nothing is known about the subjects. What happened to this beautiful couple, to those three schoolgirls solemnly joining hands in some secret pact? We don’t know. Yet here they remain, forever young.

I come to an exhibit dedicated to the Righteous Among Nations. A portrait of Raoul Wallenberg features prominently. Another section is dedicated to Sophie Scholl and the White Rose Resistance. I browse the 10,000 names inscribed on a wall, grouped by country. I look for and spot the name of Corrie ten Boom.

I’ve heard the argument passionately made by some Jewish writers that there’s something unseemly or inappropriate about films like Schindler’s List, which tells a story of Jews saved, when the Holocaust should primarily be remembered as a story of Jews dying. I have always respectfully disagreed. These thousands of names, including the names of many Christians who joined the Jews in death, remind me why.

Nearby, I learn another bit of little-known history, about the Palestinian-Jewish parachutists who joined the British army and parachuted behind enemy lines in German-occupied Europe. One of them was a young poet named Hannah Senesh. Captured in Hungary, she refused to reveal information under torture. Before she was executed on November 7, 1944, she wrote a few last lines:

I could have been twenty-three next July;

I gambled on what mattered most,

The dice were cast. I lost.

There is an exhibit dedicated to the founding of Israel, with a facsimile of the Israeli Declaration of Independence. When you read Jewish history and literature, you find that the Jews themselves were bitterly divided over the idea of a Jewish state. To this day, some of the ultra-orthodox will disturbingly side with Israel’s enemies. But the purpose of that state has never been more clear. One need only walk the streets of London and see the white fuzz where hostage posters have been torn down, then travel to Israel and see them all untouched, every one.

By now I’m running out of time and can only catch a bit of the survivor testimony video that’s playing in a small theater area. Some young students are watching in a group. I hope to myself that perhaps this will have some effect, perhaps it will counter-balance whatever they’ll find on TikTok.

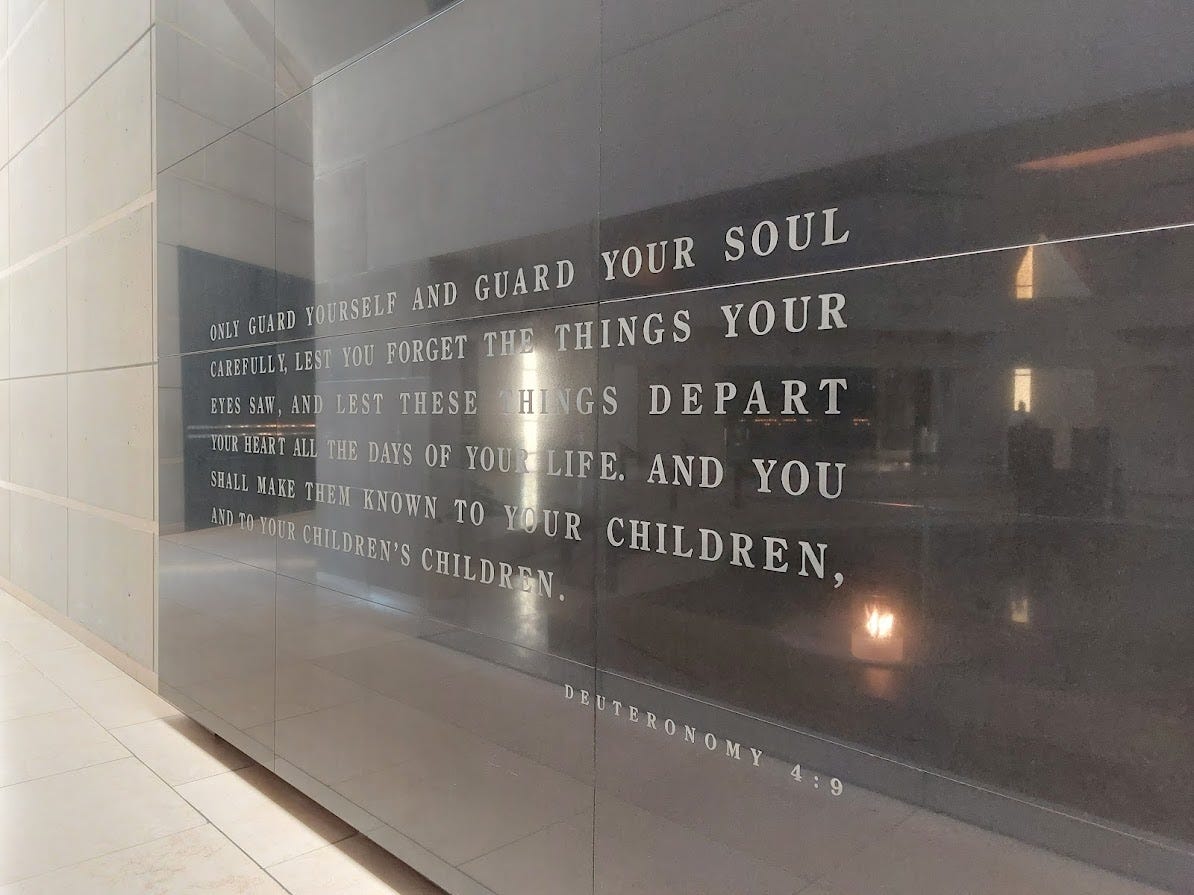

I come to the large memorial area with rows of candles, organized by death camp. The stones are etched with words from the Torah. From Genesis: “What have you done? Hark, thy brother’s blood cries out to me from the ground!” And from Deuteronomy: “Only guard yourself and guard your soul carefully, lest you forget the things your eyes saw, and lest these things depart your heart all the days of your life. And you shall make them known to your children, and your children’s children.”

Have we, though, I wonder? We have certainly tried, we are trying, but how well are we succeeding?

The museum provides a touching answer in the form of a mosaic filled with children’s art. One picture depicts a candle, with the caption, “The candle is still burning.”

It’s a cliche, but it means something. On ts Memorial Day, let us each resolve, in our separate ways, to keep the flame alive.

Nicely written. We can only bear to remember in one context; otherwise it is too much for a human to face. For that reason I agree with you that the stories of resistance are important, providing in a small way some of that context. But I think we often tend to over-idealize the resistance. In a Jewish ethics course in Div School I had a professor, a rabbi who was the son of Holocaust survivors; he wrote a book, "Morality after Auschwitz" (Peter Haas). A point that sank in for me was that the preparation for the acceptance of the Holocaust by the German people began long before the actual killings began. And the pathway was a gradual one consisting of one small self-interested decision at a time, made on an individual level. The same, he said, is true of resistance: just one small gesture at a time that relocates us and makes our next decision a tad more likely to be resisting. No great heroes and no inherently evil men; not a tragedy but sheer colossal banality: just people not realizing how every day decisions determine who and what we are continually becoming.

Dear God. Never again. My family history is Protestant, Irish Catholic, and Jewish. Let us love one another.