Objective Morality: A Tom Holland Tweebate

This house believes objective morality is, in fact, a thing.

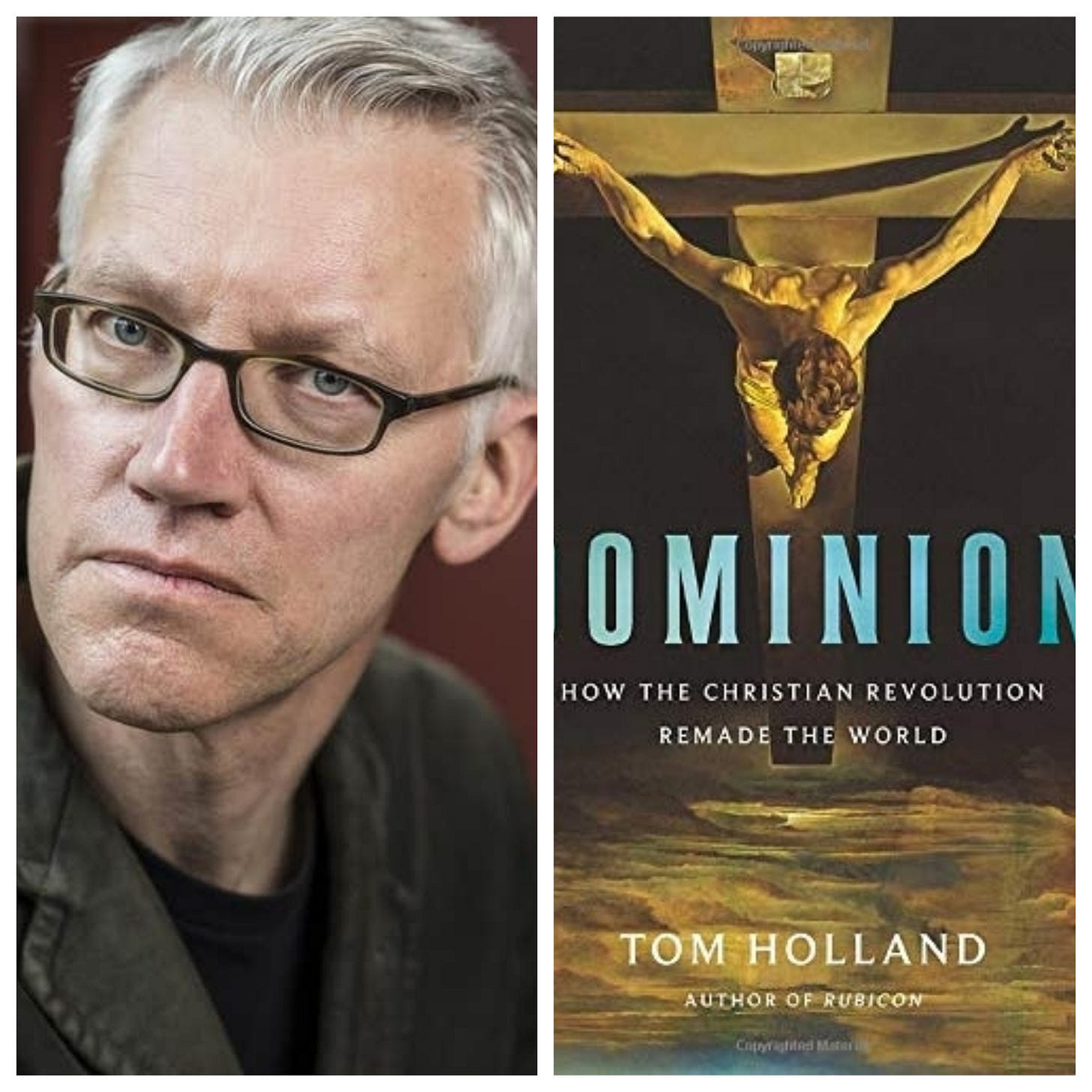

Last week, I pulled together some thoughts about the recent discourse around resurfaced comments by Richard Dawkins on selective abortion. I took issue with the framing of Tom Holland’s Twitter response to the controversy, where he maintained that human rights do not “objectively” exist, and hence Dawkins is recognizing that it is no less a “theological” proposition than Christ’s resurrection. As Holland develops at length in his book Dominion, we are culturally conditioned to believe that human rights objectively exist, but this is only because as Westerners we are downstream from the “Big Bang” of Christianity. Needling self-styled “secular” humanists for borrowing their morality from religion has accordingly become his brand. “But it’s fine!” he’ll then say, “I do it too! We’re all subjective together.”

Tom is wonderfully active on Twitter, so he and I enjoyed a little back-and-forth at the time, which I folded into that piece. Unsurprisingly, Tom remained unconvinced upon reading it. A response from fellow tweeter John Masters catalyzed yet more back-and-forth, which wound up being very interesting, at least to me. Twitter is not the ideal forum for such a rich debate, to say the least, but Tom and I both use it like people who are accustomed to developing our thoughts in complete sentences at essay or book length. (For me personally, it reminded me of the charge I used to get out of playing blitz chess as a youngster. It was hardly the context where I did my deepest and best training, but it was a helluva lot of fun. My preferred MO was to sacrifice three things in a row, set fire to the kingside and deliver mate on move fifteen.)

So, shamelessly, I decided to turn Tom’s and my little blitz round into Content, in hopes that somebody else besides me also finds it fun. I’ve tried to gather up and preserve the sub-threads faithfully and in order as they sprouted and branched off, with multiple tweets “bunched” for ease of reading. My editorial asides are bracketed in bold. Herewith, enjoy… The Great Tweebate.

John Masters: Having reviewed both our conversation, your conversation with @holland_tom and the article you just posted on the topic, I confess I still don't quite understand your criticism of his take on human rights as culturally contingent. As an atheist, he cannot acknowledge the moral truths presented by Christianity, as he has not accepted the means by which those truths are legislated. You could contest him on that point, if he had regarded those moral truths as somehow objective regardless (i.e., New Atheists). But his position that human rights (as conceived by Christianity and inherited by modern secularism) are culturally conditioned is not only consistent with his starting premises: it's the only conclusion he can reach. There cannot be morals in a world of spaces and objects alone. As observed by Yale Law School professor Arthur Allen Leff: "If He does not exist, there is no metaphoric equivalent...nothing is equivalent to an actual God in this central function as the unexaminable examiner of good and evil." (p. 1232, Unspeakable Ethics, Unnatural Law). You may argue this proves the necessity of Christianity, or at the very least, of some sort of higher principle in which morality is grounded. And I would agree. But criticizing @holland_tom for following the logical consequences of his convictions does not address the key issue.

To take your example of mathematics, if someone's conception of reality results in 2 + 2 = 5, you cannot correct them by simply showing the correct sum. You must first address what they have misconceived about reality, and from that, address their error.

[Here is the Leff article. For counterpoint, I recommend this short article by philosopher Lydia McGrew on human exceptionalism in the public square, which crystallizes, distinguishes and clarifies a number of the questions at issue specifically when it comes to human rights.]

Tom Holland: I agree!

Me (initial response to John): In that case, the thing that someone has misconceived about reality is the fact that 2 + 2 = 5. Genuinely not sure what you have in mind by way of "correction" that wouldn't just be a more roundabout way of saying "K but 2 + 2 = 4 tho."

To your broader point, we hold all sorts of people accountable for all sorts of things whether or not their "worldview" logically allows for it. Why? Because "they knew better," i.e., they have epistemic access. I think this is a common confusion people get hung up on, saying that you can't have epistemic access to something unless you accept all the ontological conclusions that something entails.

Me again (to Tom): This might be an interesting clarifying question for you (if you'll indulge): What *is* an example of something "objective," in your view?

Subthread #1:

Tom: In the field of history, I would give as an example of an objective truth: people who don't eat starve. As examples of subjective, culturally determined truths, I would give: babies not fit to become Spartan warriors should be eliminated; abortion is wrong.

Me: Okay, so this is interesting—could we add "Jewish genocide is wrong" to the column of "subjective/culturally determined truths," since we've seen more than one culture rise up which is bent on that goal? Not meant as a gotcha!

Tom: Of course. (Links Unherd piece titled “How Hitler Killed the Devil,” with tag “In a world without God, the Führer is the ultimate benchmark of morality.”)

Me: I certainly agree with the thesis in the tag here when I've heard you articulate it (I even find it rather profound). I confess I fail to see the through-line to "And therefore there exists a possible world in which Hitler isn't wrong actually."

Tom: But if you'd been born and raised in a Germany that had won the War you almost certainly would. That your parents are Christian has, I suggest, had a certain impact on the beliefs that you view as being immutably objective. Had they been Nazi, who is to say the same would not have been the case?

Me: And indeed, we can go directly to Germans in our own timeline who backed Hitler. So the key question: Were they rejecting a subjective truth? Or an inconvenient objective truth?

The searing of consciences is an inter-generational business, certainly. No disagreement there! But riddle me this one: How come Michel Houellebecq sees "death with dignity" as a grave evil, but countless priests and rabbis don't? (I link Unherd’s English translation of “How France Lost Her Dignity.” ) I'm really keen to get your take on this one, because if you'll pardon my French, this completely screws with your categories here.

Tom: Because Houellebecq despises post-modernity and yearns - vainly - for the sense of absolute truths that Christianity would once have given him (see Soumission), whereas churches & synagogues have long been marinaded [sic] in post-modernity.

Me: Or perhaps... he's yearning for absolute truths, period, while at least the churches and synagogues he lambastes have forgotten absolute truths.

[Sub-thread fizzles out here, but I think my point stands. I agree with Tom, of course, that the seminaries and the synagogues have been hijacked by post-modernism. However, I think this exposes a crack in his thesis, because growing up “downstream of Christianity” and even being saturated in a Christian background/Christian thought doesn’t seem to have kept numerous priests from plunging with abandon into the abyss of “assisted dying,” abortion rights activism, etc., etc. Self-styled “Christians” have written at academic length even putting forward arguments that people can “lose” the imago Dei. All of the above is most simply explained by the thesis I’ve been putting forward this whole time: Morality is objective, it is discovered not created, hence it is “open-access” for all, just as the geometric proof was accessible to the slave-boy in Plato’s Dialogues. But, because man is corrupt, with sufficient motivation anyone is capable of looking the other way.]

Subthread #2, me continuing from my question about what Tom conceives of as “objective” knowledge:

Me: Do you naturally tend to class the "objective" with the scientific, say? This may not be you, but it's something I tend to notice generally, that "objective" = "that which we can measure, experiment on, put in a test tube, etc." But if it comes down to it, I have *less* direct access to the material realm than I have to the moral realm. I can be 100% certain, Tom, that *if* you exist, it is wrong to kill you. I can't be 100% certain that you exist, however!

Tom: I feel like Dr Johnson - I have an urge to kick a stone.

Me: And I don't in fact think the problem of the external world is a problem (though it *is* fun!) Dr. Johnson can know beyond reasonable doubt that the stone exists. But, if we're grading on a spectrum, he knows *more* surely that it would be wrong to throw it at a dog.

(Tom aside: Arrant sophistry, and there’s an end on’t.

[Well, I never! But seriously, I fear Tom may here have mistaken me either for an idealist or for a radical skeptic about whether we can “know” anything at all beyond sterile tautologies. I am neither!])

Me (continuing): I made the analogy to maths because I think you'd agree we're not *really* holding our breath to see whether *enough* people decide that 2 + 2 = 5 that we'll suddenly have to take them seriously. Because we know we wouldn't, and shouldn't. Same with moral truth, I would assert.

Tom: But as I said, if people in other periods of history have thought & demonstrated to their own satisfaction that 2+2=5, then our belief that 2+2=4 will rank as a culturally contingent one.

Me: Perhaps our *belief* is culturally contingent, in the sense that if you asked "Well, why do you have this belief?" we'd point to nursery school, etc. But that wouldn't change the fact that one of these beliefs corresponds to reality, and the other doesn't—no?

To go back to your original tweet, in one sense an honest humanist could say, "I see human dignity in weakness because the story of a crucified God has conditioned me that way." That can be causally true. But, also, he is apprehending something outside of himself and his culture.

Summing up: The *belief* may be a product of cultural conditioning, yes. But, if we're believing a true thing, we've discovered a fact, which fact is not a product of anything, or subject to any change. It simply is. If this is also what you meant all along I will be so happy.

Tom: Sure. But then the obvious question: IS it true?

Me: Well, try kicking a stone. What does your toe tell you?

But to be serious: Truth isn't in the habit of waiting around to be discovered before it becomes true. This is why I don't see the ultimate *substantive* value in gesturing to the Spartans, or the Romans.

(Of course if by "it" you mean "Is the entire story of the dying and rising God true?" I would also say yes, but that's a proposition with a few more moving parts to unpack and justify than "Killing babies is immoral." — which is true by the natural light.)

Tom: Looking at the broad sweep of history, and at a world where China will most likely be the greatest power, I feel pretty confident that the concept of human rights is a very precarious, fleeting &, yes, culturally contingent one.

Me: Goodness, we don't even have to go to China—look at the comments under my own bloody Spec article! That was my point. But why is it so precarious? Not because there's a question about its truth. Rather, because it's a damned inconvenient truth.

Again, we are in agreement that belief (or lack thereof) is shaped by culture. As I pointed out in the Stack, in Iceland today the culture has conditioned women to believe they should abort their babies with Down's syndrome. Cultures can sear their consciences on a mass scale.

Tom: I feel we are going round in circles here! Neither of us accepts the premise from which the other is arguing. And I must return to Nero's Rome.

Me: In that case farewell, but do be careful, I just heard a fire truck going that way!

(Although, I can't resist asking because I genuinely don't know—from what premise do you think I'm arguing?)

Tom: I am not entirely sure, because I lack the grounding in philosophy to understand it.

Me: Well, I certainly hope I can state it without devolving into a mess of philosophy jargon! I suppose the purest distillation would be that truth is always true whether we agree upon it or disagree upon it, love it or hate it, build a society on its acceptance or rejection.

The analogy could be made to a beautiful painting which does not diminish in beauty, nor a great play in its quality, depending on whether it has a gallery full of spectators or a rapt audience of one.

Tom: Again, taste is culturally contingent.

Me: *Taste* yes. But taste =/= quality.

[We interrupt this program to bring you breaking news that Robert Pirsig just called, he wants his motorcycle back.]

Encore:

I add a very short followup from the next day, which I think is of interest here.

Me: More chewing on yesterday's tweet-flurry with @holland_tom on the existence/non-existence of objective morality. One small clue I neglected to raise: Why is it that little children have to be conditioned to accept abortion but never the other way round? It doesn't really matter if a given little child has Christian parents or no. Their initial basic instinct is to celebrate "baby in Mum's tummy" as a good thing. If you explain the basic mechanics of what an abortion is to them, they are shocked/horrified. Given that abortion became normalized in our culture long ago, the child's first instinct is, if anything, counter-cultural. How then, could it be culturally conditioned?

Tom: Why is it that Jeremiah had to condition the people of Judah not to offer child sacrifice, but not the other way round?

Me: But there you're talking about adults participating in an accepted cultural ritual. The true parallel there would be to Western adults today who accept abortion as a sometimes necessary "sacrifice." My clue specifically pertains to a child's first moral reasoning.

John Masters chiming in: Argument from instinct/feeling is a sword without a hilt, as you will be inevitably confronted with an instinct you very much want to keep under lock and key, and conflicting instincts which seem equally valid (I believe Lewis makes a similar argument, though I forget where).

[I missed this tweet at the time, but replying here, I’m unsure which Lewis work John is alluding to, but Lewis most certainly understood natural law, the Tao, etc., and indeed devoted an entire book to it (The Abolition of Man). To address John’s objection, nothing in my argument contradicts the trivially true point that as fallen creatures we have both ignoble and noble instincts/feelings. But his point doesn’t refute my claim that we still have a God-given moral sense, a conscience — which, yes, we are certainly capable of searing, as I’ve acknowledged multiple times here. However, it may be this side disagreement traces back to a deeper divergence of Christian anthropology, where some traditions will claim our faculties are so wholly corrupt that we can’t trust any natural instincts whatsoever to be in correspondence with truth, hence we are forced into some form of divine command theory where we exchange all intuition for direct revelation. I don’t grant this.]

Update: Many thanks to the lovely Susannah Black for pointing out that in fact John was thinking of a bit from The Abolition of Man, which I shall now quote. But I definitely don’t get from this bit that Lewis would reject objective morality, which would be orthogonal to everything the work is about and everything Lewis was about:

Each instinct, if you listen to it, will claim to be gratified at the expense of all the rest. By the very act of listening to one rather than to others we have already prejudged the case. If we did not bring to the examination of our instincts a knowledge of their comparative dignity we could never learn it from them. And that knowledge cannot itself be instinctive: the judge cannot be one of the parties judged: or, if he is, the decision is worthless and there is no ground for placing preservation of the species above self-preservation or sexual appetite.

If you made it to the end of this little adventure, many thanks for reading! Commenting below is reserved for paying subscribers, so please consider subscribing for this perk as well as regular paid-subscriber-only content.

I'd forgotten how much fun this one was! I also feel like I need a PVK-type post game analysis / commentary on what was going on with each remark & reply. "Here you see Holland is using the Evans Gambit..."

Tom says "we are arguing from different premises...but I don't know what yours is.." Wha? What are his premises? Where is he hanging his skyhooks from?