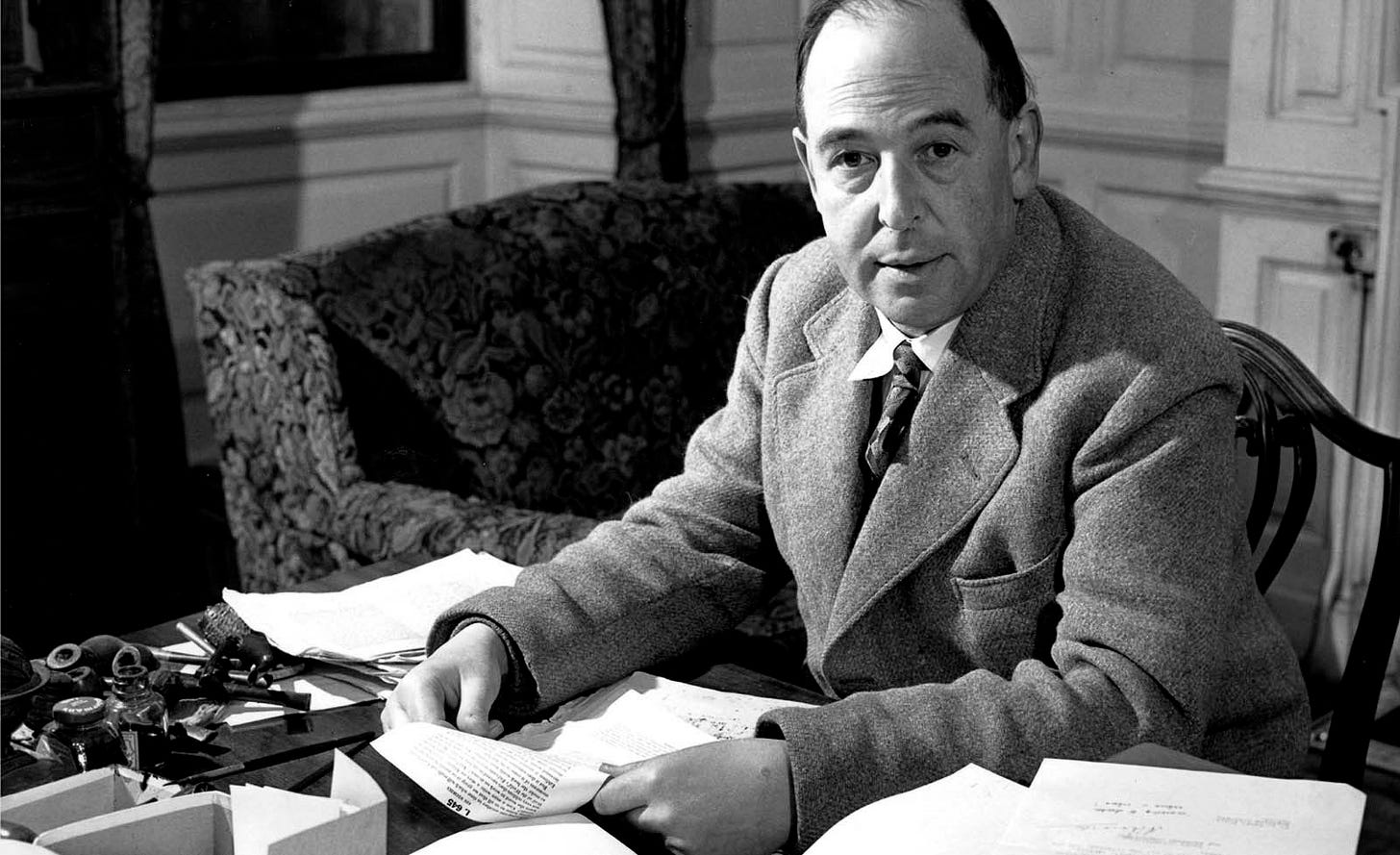

Saint Clive, the Honest

A deathaversary appreciation

Today marks the 60th anniversary of C. S. Lewis’s death. Some fine tributes are starting to circulate. (Check out this article by Rhys Laverty in The Critic on Lewis as Prophet.) I missed various magazine deadlines to submit a polished long-form tribute of my own in time—ironically, partly because my year was consumed with work on a major Lewis-related project, on which I hope to be able to say more later. But the nice thing about having a Substack is that I can share unpolished thoughts any time, in the reasonable hope that at least some of you will graciously read and enjoy them.

This little Substack owes its name (Further Up), its logo (a lamppost) and much in its content and style to C. S. Lewis. It’s fair to say that without having been steeped in Lewis’s work as a child and a young adult, I wouldn’t be half the writer or the thinker that I am today. The descriptor “Lewisian” will always be one of the highest compliments I can give or receive. When I think about what exactly I mean by this, among other things I think of pastor John Piper’s apt description of Lewis as a “romantic rationalist”:

He combined what almost everybody today assumes are mutually exclusive: rationalism and poetry, cool logic and warm feeling, disciplined prose and free imagination. In shattering these old stereotypes for me, he freed me to think hard and write poetry, to argue for the resurrection and compose hymns to Christ, to smash an argument and hug a friend, to demand a definition and use a metaphor. It is a wonderful thing when a great man shows a struggler how to be himself.

Being exposed to Lewis early and often powerfully inoculated me, as it did Piper, against this false dichotomy. While it’s never too late to start reading him, I feel lucky to have discovered him in what seems to me the ideal way—slowly, starting with Narnia as a child, then working up to other parts of his bibliography as I became old enough to appreciate them. The wonderful thing about Lewis’s work is that you grow into it. Some works, like That Hideous Strength, Til We Have Faces, and A Grief Observed, are things you return to with the passage of time, realizing they were even better than you thought on first read. I think of the scene in Prince Caspian where Lucy encounters Aslan after a long absence and says he seems bigger. “That is because you are older, little one.” Every year she grows, she will find him bigger, not because he is changing, but because she is. Like Lucy, I grow older. And each time I encounter Lewis, I see things I never saw before, things that strike me in new and deeper ways.

Lewis is much-quoted, for good reason: He is prolifically quotable. (There are also a few famously misattributed quotes, like “You are a soul, you have a body,” which no doubt would have annoyed him greatly.) And yet, there’s a paradoxical sense in which his quotability almost risks watering down his true value as a thinker. There’s a temptation to see Lewis as a one-stop “Christian answer man,” the super-Christian who always had the perfect eloquent solution to every Christian’s hard problems. To be sure, he came closer than most Christian writers to providing a sense-making framework for hard problems. But even he wouldn’t claim to have “solved” them. Indeed, his very strength as a writer was that his work swung free of top-down systematic theologies which claim to provide comprehensively satisfying theological answers.

I noticed an example of this watering down some time ago on Facebook, when someone was sharing an excerpt from A Grief Observed. “What reason have we, except our own desperate wishes, to believe that God is, by any standard we can conceive, ‘good’? Doesn’t all the prima facie evidence suggest exactly the opposite? What have we to set against it? We set Christ against it.” And there the quote neatly ended. This greatly irked my mother, who practically has Lewis’s corpus memorized and knew how the passage immediately goes on:

But how if He were mistaken? Almost His last words may have a perfectly clear meaning. He had found that the Being He called Father was horribly and infinitely different from what He had supposed. The trap, so long and carefully prepared and so subtly baited, was at last sprung, on the cross. The vile practical joke had succeeded.

What chokes every prayer and every hope is the memory of all the prayers H. and I offered and all the false hopes we had. Not hopes raised merely by our own wishful thinking; hopes encouraged, even forced upon us, by false diagnoses, by X-ray photographs, by strange remissions, by one temporary recovery that might have ranked as a miracle. Step by step we were ‘led up the garden path’. Time after time, when He seemed most gracious He was really preparing the next torture.

That won’t fit on a needlepoint, needless to say. To quote my irked mother, “Let Lewis have his dark moment!”

“I wrote that last night,” Lewis comes back to say—perhaps not strictly true, but part of the device of the work. “It was a yell rather than a thought. Let me try it over again. Is it rational to believe in a bad God? Anyway, in a God so bad as all that? The Cosmic Sadist, the spiteful imbecile?” He proceeds to confront the question head-on, less emotionally, but no less forthrightly. The chapter doesn’t exactly end on a triumphant note: “It doesn’t seem worth starting anything. I can’t settle down. I yawn, I fidget, I smoke too much. Up till this I always had too little time. Now there is nothing but time. Almost pure time, empty successiveness.”

And this is why so many of us love Lewis—not as the super-saint, the answer man, the omniscient guru, but as a fundamentally honest writer, continuously working out his own theology. “This is what I think,” he seemed to be saying, “Now go and think some more.”

This is what I aspire to, as a writer who’s had the privilege to see my work reach an eclectic audience and received some touching responses from people who tell me it’s been useful. Like Lewis, I’m thinking hard about hard problems. And if, like Lewis, I hope to be honest, then I have to admit that I don’t have full solutions. I have what in mathematics we would call “partial results.” But for whatever they’re worth, I offer them. They are yours to consider, to turn over, perhaps to discard, or perhaps to build on. Whatever you do with them, I hope they are of some value. And if they strike you as especially wise, chances are good C. S. Lewis said it first.

After losing my baby boy, reading A Grief Observed has been like speaking with the only person who has felt what I've felt and thought what I've thought after experiencing the same devastation.