The Conference of Misfit Souls

Dispatches from the meaning crisis

I am recently back from a full weekend in Chicago, where I attended an intriguing little experiment in conferencing called “Midwestuary.” Speakers included Rod Dreher, Jonathan Pageau, John Vervaeke, Elizabeth Oldfield, and Christian Reformed pastor Paul VanderKlay, who’s not a household name in establishment spaces but has gained a large YouTube following. When people have asked me what the conference was all about, I have to think a bit before answering. This long post will be my less than perfectly organized attempt to capture the idea, the people who made it come together, and the many things it gave me to chew on. First, let me back up and give (the short version of) the Internet history behind it.

Paul VanderKlay and I first crossed paths back in 2018, when we were independently making commentary on the rise of Jordan Peterson. We come from different streams of Protestantism, so it took a little time for us to get comfortable with each other, but I’ve found much to appreciate in Paul’s work, and hopefully the feeling is mutual. As Paul’s sphere of influence has widened, he’s become affectionately known as “the Internet’s pastor,” warmly welcoming the sort of people who have time to watch hours of YouTube commentary on religion and philosophy, social studies, and the history of ideas, then argue on Discord about it. Some don’t have a religious background but became “religion-curious” under Peterson’s influence. Others are in the church but struggle to find church friends who are as nerdy about this sort of stuff as they are. Some just struggle to find friends, period.

I fondly remember those first few years when I had the time to jump into those endless Discord threads myself, trying to keep my finger on the pulse of what was happening in this little corner of the Internet. I was full of (in hindsight) over-optimistic zeal about what evangelistic harvest could be reaped there, although I like to think I played a role in the conversion of one young Dutchman (named Job, symbolically enough). The truth was, I was looking for more friends myself. And while many of my connections were temporary, I made a few that have lasted, really lasted. There was something about that Petersonian butterfly effect, something about the discussion space opened up around VanderKlay’s channel, that attracted the kind of person who was my kind of friend.

There are many possible reasons for this, but I think one is that Peterson modeled sincerity, in a time when sincerity is uncool, but many secretly crave it. I might have found his intellectual project to be in various respects a misguided muddle, but I could never doubt that he was in earnest, and that he cared about people. (Read more of my reflections on Peterson’s arc here.) By extension, I think people in “this little corner” understand the importance of being earnest. Simply, they want to talk about real things that really matter.

An estuary is by definition a transition zone. It’s a place where freshwater and seawater mix together. This has become a symbolic image for the peculiar bits of community that have begun to form in this space. Over time, those bits of community have escaped Internet space to become something incarnated and three-dimensional, in a church here, a bar or a coffeeshop there. The “estuary protocol” is simple: Everyone brings an idea to discuss—it could be something you read, something philosophical, something personal, whatever you feel free to share. A group leader goes around the circle and invites each person to put his idea on the table. Then everyone “points” to an idea not his own that catches his attention. Generally, one or two ideas will emerge as the ones with the most “juice” to get something interesting started. Then conversation flows from there, gently guided by the leader but ideally not requiring too much steering as people find a rhythm with each other.

Of course, there will inevitably be That Guy who wants to fight about the hot-button Discourse of the day. People will tend to “point” at something else, because people are looking for something else. But estuary isn’t necessarily all kum ba ya. It can function as an arena where people relearn how to debate something touchy with a flesh-and-blood opponent who’s sharing physical space with you, not a disembodied avatar. As I’ll discuss in a minute, two speakers modeled this on stage in a conversation about one of today’s hottest hot topics.

For people who come out of churches that do small group, “estuary” will sound like a variation on a familiar theme. The twist is in that fresh-saltwater blend: These groups can be a potpourri of folks with some religious background or none, and politics potentially all over the spectrum. They provide a space for people to formulate questions that might create a record-scratch moment in pleasant churchy chatter. The only requirement is a willingness to listen.

Midwestuary was an attempt to take this “estuary protocol” and see whether it could scale at the level of a conference. There’s a certain accepted format for a conference: People show up, they sit in an auditorium listening to some lectures, then they have lunch, then they go back to the auditorium to hear the speakers talk some more. In between, there might be pockets of time to buy a few books and stand in line to get them signed. And after a day or two of this, it’s all over. Maybe the lectures go up on a YouTube channel later, and as you play them back, maybe part of you wonders why you got on a plane or a train to go hear them in person. Generally, the answer is that you made some connection with a fellow attendee—maybe someone you knew already but only online, maybe a new friend. Speakers are cool, but in a way, speakers are “bait” to make people clear their calendars and converge on the same physical space for a day or two. It’s in that convergence that the most interesting stuff is usually sparked.

The Midwestuary organizers designed the event with this fact in mind, by taking the time between speaker talks and putting estuary structure around it. All 350+ attendees were randomly divided into small groups of roughly ten people each. No one was forced to show up for every 60-90-minute meeting of their cohort, but almost everyone did. Even speakers were invited, if they felt like it. (I hear Rod Dreher fully participated in the estuary spirit and attended each meeting.) Because these groups were randomly assigned, it created a delightful “box of chocolates” effect, mixing people up across ages, denominations, and faiths. Unless I’m mistaken, everyone in my own group was a Christian of some stripe, but something like a third of the attendees were areligious—a function of the fact that the speaker lineup wasn’t composed of “establishment” names in any particular Christian tradition. I heard that this created some fruitful tension in a group where a few evangelistically eager Christians were flung together with people less than eager to be evangelized. The protocol forced them all to spend quality time getting along with each other anyway. In another group session, I heard that a couple of theology nerds were hoping to spark some discussion about the finer points of eschatology, only to be eclipsed by a skateboard bro who wanted to discuss the essence of “coolness.” One follows where the spirit of estuary leads.

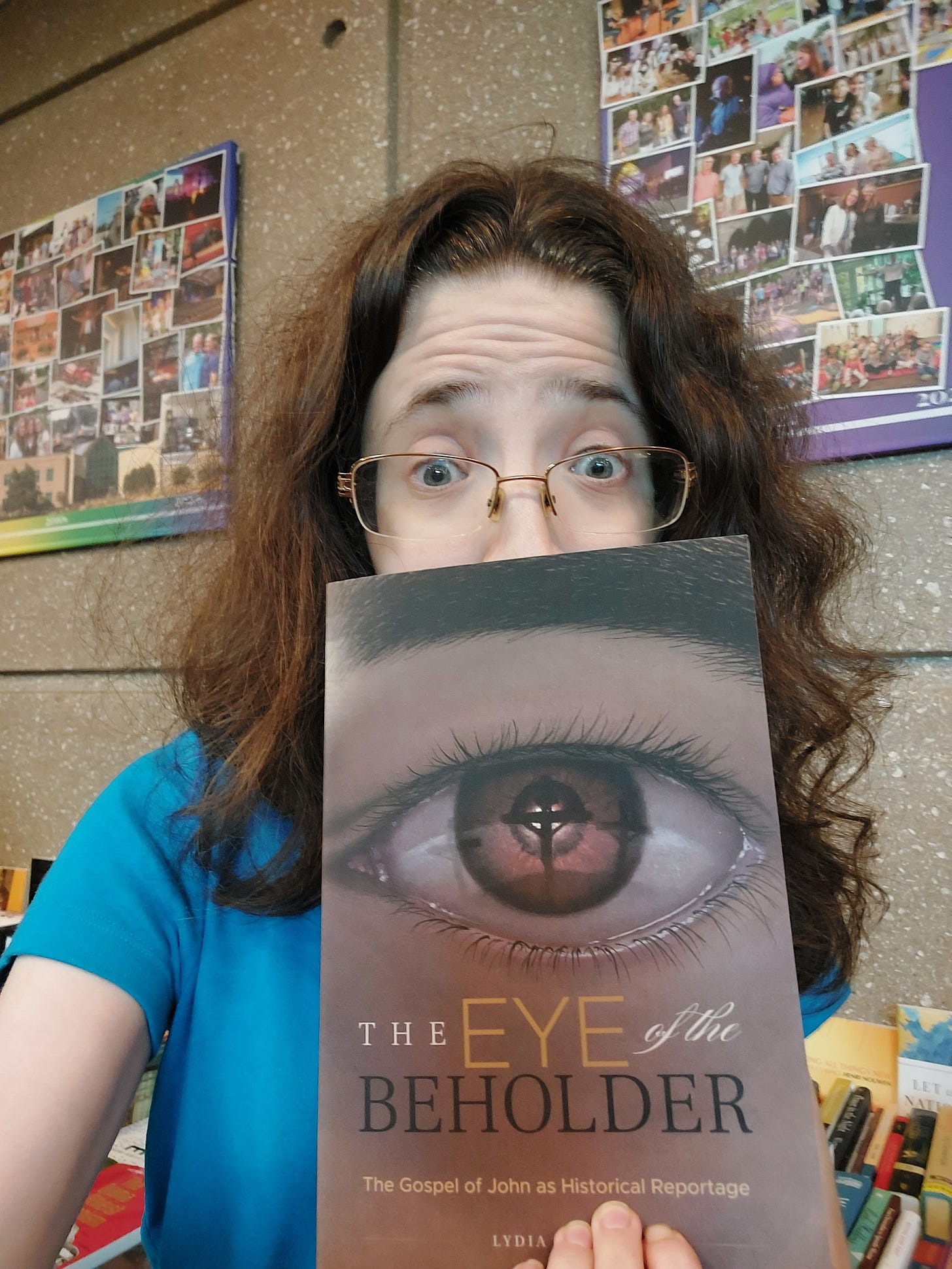

It wasn’t a perfect experiment. Conferences are normally planned with institutional backing, but the folks putting Midwestuary together are self-described “amateurs,” a group of Chicago friends who’ve been hanging out together for the past however many years, then decided to start a non-profit and just go for it. But secretly, they happen to be an unusually competent bunch of guys, and for all the typical hitches and hiccups that attend this sort of thing, it showed. The church venue was ideal, a spacious building full of quiet rooms and nooks for our small estuary groups to scatter themselves. The food was plentiful and high quality. The coffee was bottomless. The book tables were filled by the Eighth Day bookstore, including works by the speakers, but also including a wide array of classics and current works. I helped myself to a beautiful edition of Winnie the Pooh and a small collection of Dorothy Sayers’ poetry. I was also delighted to realize that three of my mom’s New Testament books were in the mix. Of course I fulfilled my filial duty and managed to sell people one of each.

To give the rest of this review a faint semblance of organization, I’ll divide it into thoughts on the pre-conference, the main event, and the aftermath.

Pre-Conference

I arrived by train the day before, in time to attend a special dinner event with the speakers and select other attendees. It was a Supra, a traditional Georgian feast guided by a master of ceremonies who prompts the table with a series of themed toasts. This MC is called a tamada, one of several Georgian vocabulary words we learned. The feast was governed by various rules we tried to follow with varying success, including the rule that you can’t pour your own wine—a neighbor must pour for you. Our tamada was John Heers, the man who brought the Supra to the U.S. It was a night of outrageously delicious food and endless wine, plus small glasses of something extremely strong with a Georgian name I’ve forgotten. I was rather tipsy at the time.

I sat across from a young Illinois couple who fell in love cleaning a charismatic church in California together (she had day shift, he had night shift, and they kissed in the twilight, as it were). He’s now an electrician, she’s a photographer. They’re raising their young children close to his parents and currently attend an Anglican church, after a complex reckoning with their charismatic roots. They’re passionate about all things good and true and beautiful. The husband lurks online under the name “Rilian,” and you can read his lovely reflection on the conference here. He also surprised me by mentioning an old blog post I’d written about Jordan Peterson that especially stuck with him, from years ago when I was still using a pen name myself. (I would go on to meet other readers whose memory improbably stretched all the way back to that era.)

Rod Dreher was born for an event built around toasts, and he regaled the table with stories of some colorful characters from his Louisiana hometown (read here at his Substack). Paul VanderKlay for his part drew from a deep multi-generational well of ministry stories. We drank to our parents, children, friends, and the spirit of fellowship. Our lone British speaker Elizabeth Oldfield, who came to the event as something of an outsider, entered into the spirit of the thing by talking about her first experience of a Cubs baseball game that week, where she witnessed the first IRL meeting of some nerdy bros who’d only known each other online. Their excited anticipation and earnest joy reminded her of the beauty of male friendship.

Probably the most memorable story of the night was our tamada’s tear-jerking account of a bittersweet Supra one of his colleagues hosted in Seattle. A woman called full of excitement about planning a dinner for (if I remember right) her birthday. But after everything had been set in motion, her husband called back, strenuously demanding that the whole thing be canceled. He explained that there was no party. No one was coming. She was delusional, he said. And she was dying of cancer. The young planner didn’t know what to say. By now the food was coming, and it was too late to send it back. So they brought the feast to the address they’d been given—a little Airbnb. Inside, the man on the phone sat brooding and drinking: “We can’t pay for any of this sh*t.” The woman sat looking emaciated but expectant: “Oh good! You came!”

As they began laying everything out, there was a knock on the door. It was the couple who owned the Airbnb. She had invited them. A few minutes later, another knock: A Mexican delivery guy. She’d invited him too. Why not? “This is all true!” John kept saying as he told this story, “I swear this is true. This happened.” And so the Supra proceeded.

The owners of the Airbnb covered the full cost of the feast. A few days later, the woman died.

This and other stories from the night moved me to reflect on the givenness of our lives. We strive for autonomy, but in truth we live constantly in debt—to our ancestors, our friends, and sometimes, to the kindness of strangers.

Main Event

Of all the speakers, Dreher was the one I felt most aligned with and have followed most closely over the years. You can read my review of his latest book here and watch a discussion we had about it here. While I don’t agree with all his theological or philosophical turns, I appreciate the constantly open, vulnerable spirit he brings to his work. He showed up to this conference ready to welcome his fellow misfits with open arms. The conversation about how to find friendship and community isn’t merely hypothetical for him. It’s a question he is painfully laboring to answer for himself. He wrote recently that he feels like a man whose hands have been chopped off, still trying to shake hands and not sure why it isn’t quite working.

John Vervaeke, a colleague of Jordan Peterson at the University of Toronto, also readily identifies as a misfit. Like Peterson, he has a complicated and in some ways antagonistic relationship with religion in general and Christianity in particular. The phrase “meaning crisis” is his coinage. His framework for beginning to solve it is an offbeat mix of Greek philosophy, Zen Buddhism, and cognitive science. This is not my metaphysical tea, as you can imagine, but Vervaeke like Peterson brings an intense vulnerable earnestness to the table, and his unpredictability makes him a lively addition to events like this. Put him on a panel, and one never knows quite where things are going to go. In a Q & A discussion, he framed the meaning crisis as a wisdom crisis. “How many of you want to be less foolish?” he asked the crowd. (Dreher, without missing a beat: “If I were less foolish, it would ruin my brand.”)

Someone invited the speakers to discuss Peterson’s rise and clash with the new atheists, as well as his seeming inability to say he believes in God. It fell to Vervaeke to try awkwardly to answer this question, as someone who “knew Peterson before he became a god.” Despite an implication of some significant political differences, Vervaeke clearly respects Peterson as a colleague and praised his “personal courage.” It was that courage people were drawn to, he said, while the new atheists offered nothing but “smugness.” At the same time, he said Christians shouldn’t get their hopes up that Peterson is on the verge of some seismic shift that would satisfy them. For Vervaeke personally, Socrates is his “Virgil” figure, the thinker to whom he owes his intellectual “allegiance.” For Peterson, that figure is Jung. Most Christians aren’t familiar with Jung, but Vervaeke is, and he wants them to understand Jung’s deep “ambivalence” towards Christianity. Peterson has inherited that ambivalence, which leaves him perpetually in a state of religious limbo. Vervaeke relates to Peterson, but he also sympathizes with Peterson’s fans, for whom this ambivalence “can look like p*ss or get off the pot.”

Here Dreher and Oldfield chimed in with the reflection that perhaps Peterson is like many men whose identity is bound up in their intellectual prowess. Perhaps they should stop thinking so hard and surrender to the Spirit. This “left brain vs. right brain” tension was a bit of a running theme throughout the conference. (Ian McGilchrist received his obligatory namecheck(s).) I half agree, in that I think there’s something to this diagnosis, but the prescribed solution is inadequate.

Oldfield and Dreher had an entertaining chemistry throughout the event. Politically, they’re poles apart, but they have a degree of “right-brain” commonality. In another panel discussion, under the tempering influence of two moderators, they were invited to stress-test each other’s clashing views on the immigration debate. This proved so interesting that I’m actually going to save most of my thoughts about it for a post of its own next week. Suffice it to say, I align more with Dreher, but watching him and Oldfield feel their way through a frank, honest discussion of this topic was fascinating. There’s something valuable about wrestling with this sort of conversational discomfort, and it was in keeping with the spirit of the event to see it modeled well. I give props to moderators Sam Tideman and Kale Zelden for guiding it thoughtfully, interjecting their own insights along the way.

At the same time, that conversation did highlight the fact that some divides remain unbridgeable, even with the best of intentions. In a previous discussion on how difficult it is for people to make friends, Dreher had named one elephant in the room, namely that the political left has made it a point to exclude conservatives from the dinner table. In another time, Rod and his conservative friends would have happily dined “across the aisle,” but those days seem gone in an age where social embarrassment and cancellation are the norm. I wrote some about this last year during election season, reflecting on how a lighthearted show like Family Ties—where a family is internally split between “red” and “blue”—couldn’t be made today. Oldfield showed some awareness of this, acknowledging the left’s “purity tests.” But she can only make it so far across the divide. (Read Dreher’s Substack review here.)

A more philosophical clash unfolded in a three-way chat between Vervaeke, Jonathan Pageau, and Paul VanderKlay, who wanted to pick up on an intriguing Q & A moment where Vervaeke passionately held forth against the use of Large Language Models. VanderKlay teased Vervaeke for sounding like a “fundamentalist,” an instinct Vervaeke decries in religious contexts. But of course, everyone is religious about something. I cheered Vervaeke’s righteous rants about how AI use atrophies the mind and how important it is to “take the 19 hours to read a book,” to make mistakes, to not outsource the process of learning that makes us human. However, it became clear that we are separated by metaphysical differences, as he proceeded to argue that LLMs could be (unless I misunderstood him) potential persons. He wants programmers to try to align LLMs with the Good, so that if and when they achieve sentience, they can function as silicon sages, sources of wisdom.

There followed an energetic debate in which Pageau insisted that this is metaphysically Not a Thing, never will be A Thing, and for all my differences with Pageau, I have to agree with him. VanderKlay also asked an apt question: In this hypothetical world where AI bursts its silicon bonds to achieve god-like sage status, how would we know? How would we measure their supposed wisdom? If, like Vervaeke, we insist that the old religions can no longer serve as repositories of wisdom in the post-modern age (or post-post-modern), what is our yardstick?

At the same time, I see why Vervaeke winces when Pageau casually refers to a chatbot as “my research assistant.” We treat an AI in ways we would never treat a human research assistant, after all. Like Pageau, I’m annoyed when sci-fi movies try to blur the boundaries of humanness and make us care about robots. On the other hand, the way you treat a humanoid robot can still reflect something about you.

There’s also a deep connection between the rise of LLMs and the rise of friendlessness, something else Vervaeke is passionate about as a teacher who cares about lonely students and young people writing him in crisis. A big part of the meaning crisis is that people no longer understand the difference between a real friend and a disembodied affirmative voice. Just this week I saw someone on Twitter posting the latest output from one of his “conversations” with one of these machines. I suggested he should seek human connection, and he bitterly declared that no one in his life “gives a g*ddamn.” I don’t know him well, but I knew enough to be able to say that is flatly not true. Yet I couldn’t break the spell.

But there were signs of hope that weekend, not only in the conversations sparked by this conference but in dispatches and announcements about more experiments around the country (even the world, as people plan a conference in Europe). A woman from New York talked about how her small experiment had grown into a robust friend group. A forthcoming “Southeastuary” was plugged. Two young men talked about a road trip spent dipping into estuary groups around the country, then shared a desire to build or join an intentional community. Modest, small things, but many good things have small beginnings.

The conference’s final panel gave audience members a chance to come on stage for five minutes of personal Q & A with the speakers. This was a clever idea that provided a bit of tangible audience-speaker connection and encouraged people to really whittle their questions down. Some were more successful at this than others, but everyone had fun.

There were serious moments of reflection though, like when one person asked VanderKlay, “How come this feels more like church than church?” There is no doubt a whole complicated life story behind that question. Instinctively, I wanted to say, “Well, this is not church. We aren’t all part of a single body, we don’t all affirm the same creed, we aren’t subject to church discipline together.” At the same time, I knew what the questioner was trying imperfectly to capture. He was capturing the fact that just because a church gathers people together under the same creed, it doesn’t necessarily ensure that every misfit will find a place to belong. It doesn’t ensure that he’ll find people who get him, people who have time to spare for him. In short, it doesn’t ensure that he’ll find friends.

On Twitter recently, Christian researcher Anthony Bradley was mocking an article about an adult sleepaway camp—which, in fairness, had inappropriate elements that deserved mockery. At the same time, Bradley’s exasperated “Just go to church!” didn’t quite feel adequate to address the deep hunger for fellowship that drives people to experiment with that sort of thing.

Midwestuary didn’t offer the misfits any silver bullets. But it did offer them a measure of fellowship, however limited. As VanderKlay said, “Fellowship of the spirit is the incubator of the saints.”

I don’t know if he was deliberately trying to foreshadow our closing event, in which a ragtag little group of musicians strummed their way through “When the Saints Go Marching In.” (I jumped on stage for this endeavor, hopefully in a helpful way.) After we had plucked and plinked and warbled out a few verses, a professional jazz quintet appeared to usher us all out into the lobby. I found myself marching behind Dreher, who whipped out a handkerchief and twirled it around his head New Orleans style. Everyone started to dance. The Spirit was certainly moving.

Aftermath

The conference ended on Saturday, and Sunday morning found Christian attendees worshiping in various places. I visited the Christian Reformed Church where VanderKlay was guest preaching. It was an excellent service, reverent and tasteful. VanderKlay delivered a beautiful sermon about what it means to pour oneself out in small, unseen acts of service to a community. The line of people seeking to be heard is many times as long as the line of people willing and able to listen. Christians should cultivate the skill of listening.

There followed a little “town hall” where the pastor and the church asked VanderKlay various questions. This was recorded and should be available on some YouTube channel or other. It provided lots of food for thought. One older gentleman asked forthrightly whether this whole community-building experiment is too wrapped up with Internet culture. VanderKlay gave what I thought was an excellent answer, talking about how the folks at his own church back home couldn’t care less about his YouTube channel. Many of them are elderly African-Americans, not even remotely plugged into Internet world. The funny thing is, when he hosts estuary groups bringing them together with the sort of nerdy millennials who do binge-watch him (or Pageau, or Vervaeke), it’s the wise old ladies whose discussion topics usually win out.

In other words, estuary isn’t just about bringing misfits together with other misfits who can nerd out about exactly the same things. It’s also about bringing them together with people who can share wisdom. Vervaeke isn’t wrong that the meaning crisis is a wisdom crisis. You could do much worse than seeking it out from the little old church ladies in the back pew.

At the same time, many churches are serving neither misfit nerds nor church ladies very well, something that was reflected in a poignant question from another older gentleman who felt like his denomination had left him behind. This was a common theme among lower Protestant millennials at the conference too. For too many evangelical churches, the vibe is “sage on a stage,” performance, and nose-counting. It’s blinding hot blue lights in giant conference arenas. One woman in her mid-30s spoke eloquently for her generation of burned-out Protestants: “We just want to be able to attend the church we grew up in.” (Of course, there was a paradox in that the very church building hosting Midwestuary had the exact “megachurch” aesthetic that grates on us. The fact that the building could seat hundreds of people, then find space for them to break up into small groups, was a function of its size.)

That woman and her husband are now Orthodox, though she stressed that they didn’t make their conversion lightly, nor were they simply reacting against evangelical failures. Though she had plenty to say about said failures, as a former youth leader who saw firsthand how youth ministries have been hijacked by force-fed woke programming. But she was also drawn to positive goods in the Orthodox tradition—the harmony of theology and ministry, the lack of “relevance”-chasing. She was drawn to a place where she could go to pray.

The Anglican or Anglican-curious Protestant contingent also had its representatives. I’ve already mentioned my new friend Rilian. I also hit it off with Bryan, a very sharp young filmmaker from Georgia (the state, not the country), who wants to honor his evangelical roots but is drawn to Anglican liturgy. (Check out his work here.) In a small-world moment, he introduced himself to me as a friend of a good family friend in Protestant apologetics world. (He’s also a recent graduate of Ralston College’s humanities program, and you can read his thoughtful reflections about that experience here.) I could have talked for much longer with him, like so many people I met.

It’s a testament to how rich this conference experience was that I’ve been typing for 5,000 words, and I still haven’t captured all the encounters that made it memorable for me. Like Ron, the jolly giant who plopped himself next to me as we waited for a speaker and informed me, with a gleam in his eye, that I knew him on Twitter by another name. It turned out that he was a long-time follower—completely faceless and nameless, until now. Or Josephine, the empty-nester Catholic mom who talked a mile a minute in my estuary group, overflowing with quirky ideas she couldn’t share with any friends back home. She told me how much she appreciated my writing. Again I put it together that she’s followed me on Twitter forever. Where else would I have encountered her, not as the cartoon avatar she lurks behind online, but as a flesh-and-blood person?

Then there was Hermann, a laid-back “Orthobro” in my group who revealed that he was descended from King Alfred the Great, sparking monarchy jokes for the rest of our session. I learned the rest of his story over dinner—how he’d grown up Catholic, drifted away, lit out for California to chase a music career, then returned home after finding no rest in empty pleasures. It took him a long time to settle on Orthodoxy, but after seriously weighing it with his Catholic heritage, he was convinced.

Then there was Rigel, who had the constellation Orion sewn onto his shirt pocket, with the appropriate star popping out in its own color. His parents were hippies who one day decided to pilot a boat from California to Hawaii. He was the fruit of their love along the way, named after the star that had guided them. He makes a short appearance at the beginning of this vlog by Christian Baxter—another friend I’ve made in “the corner,” with his own whole story and sweet spirit.

And after all that, I didn’t even meet our resident cartoonist, Matt, who unbeknownst to me was composing these doodles. Later he said I’m like a Shel Silverstein drawing come to life. I was touched, if slightly alarmed by the fact that I appear inseparable from my phone. I’m becoming a cyborg, just like Vervaeke warned.

I’ll close with a little vignette from my Amtrak ride back home. I sat next to a girl who looked like she was in her late 20s, short and stocky with a butch haircut under a baseball cap. She was returning to Michigan after one of a couple IRL meetings required for her mostly virtual Episcopalian seminary class. As we chatted, somehow the topic of capitalism came up. She said she and her friends were all agreed that while we accept it as the price of modern life, it wouldn’t be a thing in any system operating under Christian ethics. I cautiously said I didn’t mind capitalism myself. I’m the kid who led my parents in a spontaneous “Hip, hip hooray!” for the free market when I was five (“because,” I explained, “I really like food”). While I admire people doing “all goods in common” community life on a small scale, I expressed my doubt that it would work on a national scale. She received all this with good humor.

In my mind, I could form a certain picture of this young woman—her theology, her politics, perhaps her lifestyle. I could imagine the sort of arguments we might have in the timeline where she browses Twitter and comes across some tweet or article where I emphatically express my views on some sensitive topic. But we weren’t on Twitter. We were sitting next to each other on the train, and there was no reason for us to have an argument.

When she asked what had brought me to Chicago, and I said it was a conference, she asked what sort of conference. There followed a pause as I once again tried to sum it up. I said it was a mixed gathering of people who are curious about religion and philosophy and stuff, and need friends to talk to about it. I said it was inspired by this pastor who did a lot of commentary on Jordan Peterson (I broached his name a little gingerly, but she was chill). She laughed when I said it was a bit like a philosophy/theology Comic Con. I explained the estuary protocol and how it made the whole thing different from other conferences by drawing people into meaningful conversation with each other. I mentioned that it was all put together by a non-profit organization, which made it feel handmade and not beholden to corporate bullshit—she nodded approvingly. That sounded cool, she said.

I could tell her energy was low, so I quietly took to my phone. When I looked back up, she was napping, cap tilted over her face.

Hours later, as I prepared to get off at my station, I double-checked my backpack to make sure my phone was there. She instinctively looked over at the mesh on the back of the seat in front of me. But it wasn’t actually a pocket, I pointed out. Whatever you dropped in the top would fall right out the bottom. I had no idea what purpose it served. She shrugged. “Aesthetics.”

And on that note, we waved goodbye, never to meet again.

You’re so so good at carrying your voice and thoughts together in your writing. I loved seeing other parts of you come through at the conference, namely tipsy Bethel and sing song Bethel. I saw your tweet about how you were created in a way that allowed for you to have a unique singing voice and so I was really paying attention when you sang at the Supra and I was truly blessed by that moment. See you round the corner Bethel and thanks for the mention : )

The estuary is a really interesting concept. What I especially appreciated is that you mentioned the idea and then provided several specific examples with significant detail of how this worked, as well how Rev. VanderKlay described them working out in his setting.