Postcards From Scotland: Laurie of Old St. Paul's

A day in the past

The day after my day at West Sands Beach, my capable friend once again chauffered me from Clackmannan through Fife. The sun once again came out to smile on me. But I would spend most of this Saturday indoors, poring over the historical archives that I had flown over the ocean to handle in person.

When I first came across the story of Canon A. E. Laurie, Rector of Old St. Paul’s church in Edinburgh, I didn’t know it was going to turn into an extensive research project. But the more I learned about this intriguing figure, the more I felt I had uncovered a life that loomed larger than life—a saint whose name deserved to burn as brightly in memory as names like Henri Nouwen or Mother Theresa, yet now flickers away only in this small corner of Scotland. A wordsmithing war chaplain, who had left behind such a riveting record from the front that it unfolded in the mind like a film reel. A social critic who pledged his life to the poor of his own community, while constantly thinking and writing about how physical and spiritual poverty could be alleviated on a grand scale. A would-be intellectual and church historian who never found the time to invest in academic research, because his pastoral duties always came first. A pastor so beloved that when he died, the streets had to be closed for his funeral procession.

Could I fan this flickering memory with my small platform, modest as it was? I became compelled to try, while I was still a young writer with time, energy, and savings to invest in such a project. If I was successful, I might even make back the price of my ticket to Scotland in book royalties one day—but this was an afterthought.

Archivist Peder Aspen and his wife Margaret greeted us at their door, looking buoyant and young for their years, and immediately offered us tea. I came bearing salvaged slices of a failed redcurrant loaf cake, which has a tendency to undercook in the middle and true to form had done so once again in my hosts’ oven. I’d warned Peder ahead of time. With a twinkle in his eye, he assured me they could find a straw somewhere in the house to slurp it up. Despite appearances, it had a delicious flavor. They laughed when we told them we’d been to “the Chariots of Fire beach.” Peder asked, “Did you run along the shore in slow motion while humming ‘La da-da-da-deeeee-dum…’?”

Peder has spent the past year giving me invaluable assistance as I launch my quest, feeding me snapshots from his irreplaceable copies of the Old St. Paul’s parish newsletters. Hardly a month went by when Canon Laurie didn’t contribute a “Rector’s Letter,” even from the trenches of war. (Read samples here.) When he was honored on returning from his first tour of duty, a peer gave a speech in which he urged the congregation to publish the war letters in a book. Years later, after his death, they would finally see public light as a section in his 1940 biography, Laurie of Old St. Paul’s. But, as I would discover when I bought one of the last circulating copies of this biography and compared with my records from Peder, the letters had been abridged. They were substantially preserved, but they were missing whole paragraphs of reflection that further illuminated the workings of Laurie’s mind. They also left off and picked up again with Laurie in the trenches, not including any of the periods between tours that showed Laurie further processing and applying his experiences. Like all veterans, he carried his share of survivors’ guilt, which he channeled into still more energetic ministry on the home front.

I still highly recommend the biography, which I have scanned and uploaded to Open Library here. The author, himself a clergyman who knew Laurie in person, beautifully chronicles his life and ministry for posterity, drawing on some records that we no longer have. As Peder sadly explained to me, the archival team has never even been able to locate the originals of Laurie’s war letters. Nor have they located other effects to which the biographer apparently had access, like Laurie’s notebook of private devotional prayers. (I did still get to hold his last personal Book of Common Prayer, which had his initials on the front.)

What Peder did have was still a treasure trove. Some of it had been digitized, and some of it hadn’t. He scrolled through folders of material on his Mac, deliberating over what to put on my memory stick, because some of it might not be apt. I assured him I had plenty of space. He could copy over whole folders and let me sort through them later.

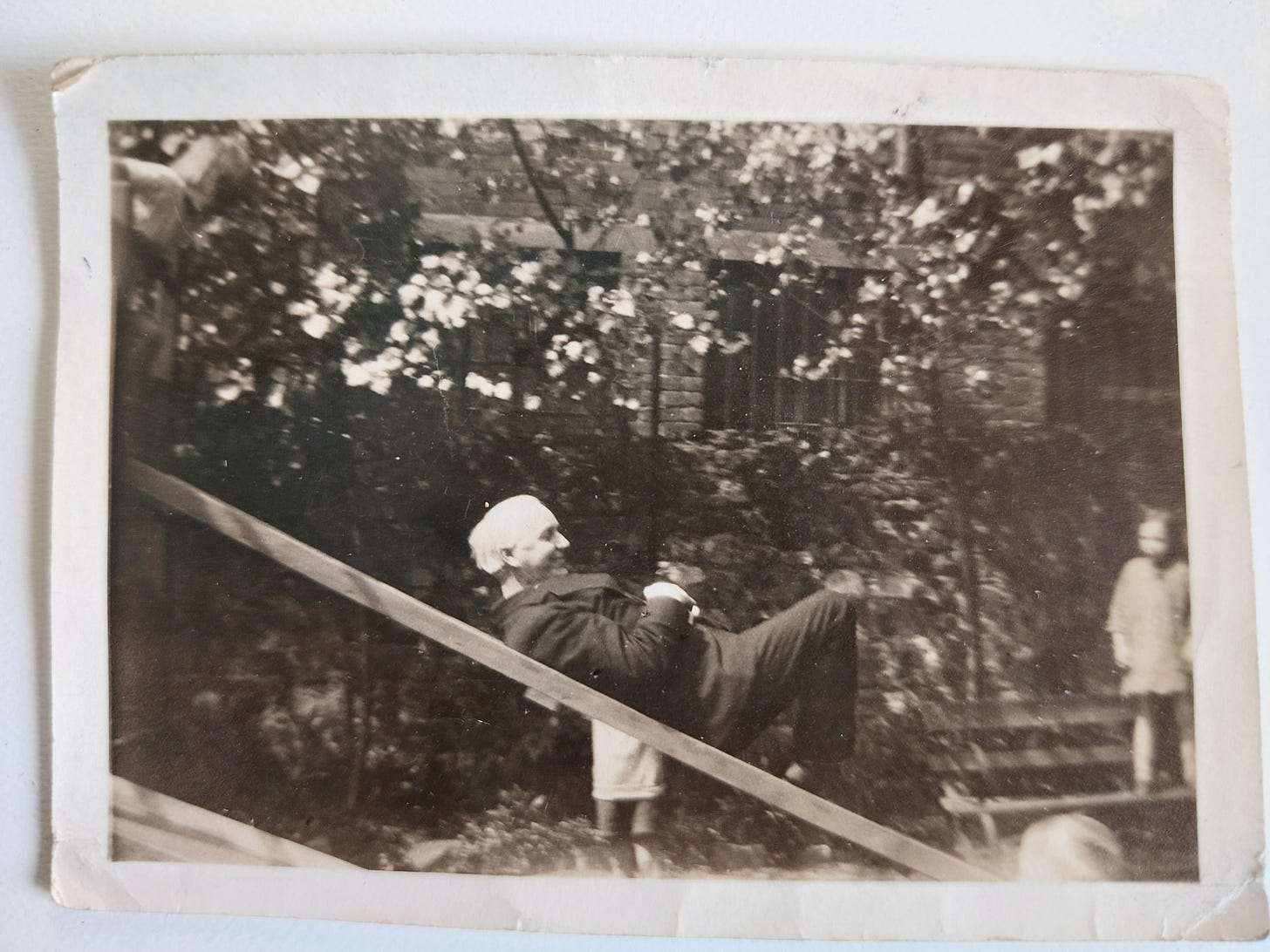

There was no way I could capture everything I had come to see on my own phone camera, so I had to be content with judicious sampling. I tried to complement what Peder had sent me already, filling in gaps, using key moments from the biography as a guide. I also allowed myself to just sit with the records, enjoying an opportunity I might never have again. In a binder, I found original photographs of Laurie that I’d never seen before, together with originals of a few I’d seen in the biography. I pulled out the crisp black and white images and held them gingerly. They were taped several at a time to thick pieces of backing material. Peder assured me I could break the tape and examine them up close one by one. Flipping some of them over, I saw a woman’s name etched in faint pencil—the photographer, perhaps? We can no longer be sure. A couple snapshots seemed to show him posing in uniform back in France after the war, gazing solemnly into the middle distance. Others showed him as an old man in the parish’s famous Child Garden, blissfully at home with the little students. One snapshot captures him going down their slide, a self-satisfied look on his face.

The Child Garden was a groundbreaking outreach experiment in children’s education, plucking tiny souls from the slums and planting them in an organized Christian learning environment. Its headmistress, Lileen Hardy, would become a more familiar name than Laurie himself, through works like Diary of a Free Kindergarten. Amusingly, Laurie was suspicious of her qualifications when he first conceived the venture, unsure that “an uneducated governess” could realize his ambitious vision with the requisite rigor. But she soon won him over, and they forged a lasting partnership. Peder showed me his records of her work, including the handwritten manuscript of Free Kindergarten and tiny labeled photographs of all the students, with captions like “Joy behaving badly!” and “Joy behaving quite well!”

There were also carefully preserved pictures the children had drawn for “Mr. Laurie,” which looked like all kindergarteners’ pictures do. They showed the Rector being greeted at a train station, in bed sick, being cheered up by visits from Miss Hardy and the children. Items in the pictures are helpfully captioned in neat pen by Miss Hardy herself, pointing out “clock,” “flowers on table,” “a book for Mr. Laurie to read,” or best of all, a present of “tulips,” which the young artist had originally spelled out as “choolips.” The text of the Diary is almost wholly focused on the children, but Laurie hovers godfatherlike around the edges. At Christmas, he disguises himself as Santa Claus, then innocently re-enters the room as “Mr. Laurie” minutes later.

Laurie never married, though Scottish Episcopalian priests weren’t bound to celibacy. Sifting through the archives with Peder, I hazard my assessment that Laurie almost seems asexual, as if he was so in love with the Church that he had no time for any other romance. Peder and I agree that it’s a dubious enterprise to read too much into lives like Laurie’s in hindsight (though his personality might tempt comparison to similarly magnetic priests like Henri Nouwen or Mychal Judge, who were in fact homosexually inclined). It would be too easy to impose a certain kind of reading on Laurie’s intense devotion to the young men he pastored. The essence of manhood constantly occupies his writing—the manhood of the soldiers, the manhood of Christ, the former as a type of the latter. When he is home between stints of service, his mind is always going back to the men, longing to be with them, haunted by the ones he couldn’t save. But such thoughts might occupy the mind of any priest as devoted to his call as Laurie was, free of the connotations a less high-minded age might read back into them—an age where intense masculine friendship is ill understood, and where so many men of the cloth have broken their paternal trust that we have forgotten what it looks like for a priest to love a boy without abusing him.

We actually have a recollection of what it was like to be Laurie’s altar boy, set down fifty years later with no name attached. Though this writer knew Laurie only for the last five years of Laurie’s life, and that just in “sporadic glimpses” between boarding school and holidays, the experience left an indelible impression:

In those days priest and server still had a private dialogue of preparation in the sanctuary before the Eucharist, alternately reciting the psalm “Give sentence with me, O God,” and confessing their sinfulness to each other. It was a privilege to have a celebrant so much older and holier turn to you and beg “you, brother, to pray for me to the Lord, our God.” I was just the latest in a succession of nervous new acolytes, trying to remember what to do when, and how to hold the cruets, but because the Rector regarded every human being as uniquely important he made you feel important. And he let you understand that God doesn’t mind if the ceremonial is a bit amateurish, so long as you do your best.

Behind and so close to him on the altar step, the server was caught up in the intensity of his devotion to, and absorption in, the Presence at the heart of the Mystery. The Consecration was the focus of his life. I sometimes had the feeling that he lived in the church, only slipping out to Lauder House for his meals, and this was perhaps more than illusion. As he grew older and could no longer trail up to top-storey houses in the Canongate, he had to let his people come to him, and he always seemed to be about, talking to someone, hearing a confession, praying before the tabernacle, or just sitting and taking his ease in Sion. Increasingly, like a lover, he could not bear to be long away from his Beloved’s house.

The writer goes on to recall vividly Laurie’s idiosyncratic preaching style—“the low crouch; the balancing act on the edge of the pulpit, while we prayed that angels in their hands would bear him up; the sudden call to attention, ‘Children!’, with a clap of the hands.” He recognizes these and other “tricks of presentation” as elements of how Laurie “played the part expected of him.” Not that Laurie was dissembling, he just understood his role as a man who carried on his profession in public, and he embraced it to the full. He had that quality common to all true lovers of mankind that “when he spoke to you, you were the only person that mattered.” The writer repeats a much-circulated story about a bedridden old woman whose flat Laurie walked into by accident while making his rounds in the Canongate. From that day on, he rolled back his 5:30 AM rise by another half hour so he could lay her fire and make her morning tea. In general, Sunday service starting times could be “elastic,” Laurie’s watch being set “by God’s clock, which is eternity.” When he did arrive, others recalled there was typically a gauntlet of back-pew beggars for him to run (he would say he knew they were undeserving of what he gave them, he “just worried about that one who wasn’t”). In all this, the writer reflects shrewdly that Laurie was too intelligent to be unaware of the temptations of “the personality cult.” He must have felt the pull of flattery, and must have taken care to guard against it.

We broke for lunch, where I got to know Peder and Margaret a little better. Peder told how his Norwegian father had been unable to return to his homeland during World War II, and so made a life in Scotland. Today, he keeps well occupied with various archival endeavors, including work with a massive 50-year-old collection for the British Geological Survey. (Later, with a shy boyish pride, he showed me a picture of himself with “my rocks.”) He and Margaret met each other in the Old St. Paul’s parish. He sounds thoroughly Scottish, and she sounds thoroughly English. She has a degree in medieval history. When she talks about how the parish first came to be after some congregants were kicked out of St. Giles, she refers to the incident as “when we were kicked out of St. Giles.” She is the consummate hostess, rushing to see that I have a new plate for my salad and cheese once I’ve finished my lentil soup. I start to demur that the plate under my bowl is quite clean, but my friend whispers sotto voce, “Just go along with it.” Margaret shrugs off our thanks for the little feast—“Just what we always have.”

When my friend and I arrived, Peder joked about how young we are, saying he’d been picturing retired museum ladies in tweed and thick-rimmed spectacles. Meanwhile, he and Margaret gently poke fun at their own age, at how their memories are going a bit, how one of them will ramble vaguely to the other about a forgotten factoid one day (“Do you remember the...the thing...the guy, he was going down...and there was a camel...”), then have a eureka moment the next day (“Hey, that guy was…”), without a beat skipped. I assure them I would have guessed they were much younger. Later, when I tell Peder I’m sure he will live to a hundred, he tells me he has “already applied for another life!” He shows me their film collection, a surprisingly eclectic mix. He’s fond of Vangelis’s soundtrack for Blade Runner. When I recommend a free documentary on YouTube, he nods and says, “Ah yes. I’ve just started watching YouTube recently. A bit late to the game, I know…”

We plunge back into the archives after lunch. My friend meanwhile makes gentle conversation over more tea with Margaret in the room next door. When it becomes clear that Peder and I will continue to be blissfully occupied for some time, Margaret whisks her away for a small tour of Dunfermline.

I tell Peder that I wish he had his own scanner, the kind my father has newly acquired where you can simply slip a book underneath it and turn the pages, then export everything as a searchable PDF. His eyes light up—he’s seen something like it at the National Library. It’s the only way he could scan the giant falling-apart collection of bound newsletters, which couldn’t possibly be placed face-down on a machine. I say in all seriousness that I would buy the scanner for him, and he waves me off with an “Och, don’t worry aboot it.”

He is so happy I have come. We chat about the material, about Laurie’s life and legacy, about how he had to adjust his hopes of a great social revolution when he came home from the war. When I make a point that pleases Peder, he’ll nod and cap it with an enthusiastic “Surely!” When I thank him for all his help, he gently tells me that “it cuts both ways, you know,” and I mustn’t think I am only learning from him. “I learn from you.”

In the same binder that holds the pictures of Laurie, I have found a couple of the only scraps of correspondence we still have in his own hand, both letters to women in the parish from later in his life. One is addressed to a woman who is sick, but clearly has the sort of personality that doesn’t take well to helplessness. Though brief and written with a little haste apparent in the penmanship, it shows the remarkable subtlety of his people skills:

June 24 1926

My Dear Miss Deas (?),

I’m so sorry to hear of your fresh chapter of accidents. It is very trying to be ill again particularly under the existing circumstances—and I can quite understand how restive you must feel seeing your mother obliged to do this necessary work. But you need not be surprised at this breakdown. I fear it is just what might have been expected when one remembers that you were barely convalesced before the last trials came upon you. It is sad for you that your mother doesn’t see the real situation—though even that doesn’t surprise me. You have been accustomed to give all your life. Your mother has grown to consider it second nature! She will feel that something is amiss when what appears the necessity that you should receive consideration (?) instead of giving it. You must not [unclear] the old lady too much. You have yourself ‘spoiled’ her. It has been a good spoiling and it has reacted upon your own character. And it is really a matter to be thankful for. For however hard it is upon you physically just now, I am sure you would hate to think of yourself as having the character that I fear [unclear] of taking everything and giving the least possible. The golden rule of life is ‘love’ & in this [unclear] love cannot be truly itself apart from suffering. ‘God so loved that he gave — & gave His only begotten.’

As to the practical steps to take you must want to settle about the house until your brother returns, and if in the autumn or winter you can get a post in Edinburgh—you must [unclear] up the house, & bring your mother to Edinburgh. I think Miss Turnbull will find a place for you in the long run.

As for the rule, it must be almost in abeyance just now. Your first business is to get well again & to accumulate if possible a stock of [unclear] health.

[unclear last sentence]

Sincerely yours A. E. Laurie

Another letter is written much more neatly, a carefully thought-out word of encouragement to a woman who’s going to be confirmed. Written only six years before he died, it’s a tiny masterpiece of pastoral communication, simple and direct but at no point condescending. By now, I am so familiar with his thought and diction that it feels I’m reading a letter from an old friend. He mentions “leaflets,” which he constantly delighted in writing up and distributing on all manner of subjects where he wanted to instruct the congregation:

22nd May 1931

My dear Nancy,

I want to send you a last message before you are confirmed, and to enclose the accompanying leaflets, which I hope you will use.

I won’t say anything more about the Service tomorrow, except that in it you remember you vow to make the Service of God the chief thing in your life, and God by the Gift of His Spirit gives you the power to keep your vow.

The chief thing I want to say to you is, that the wisest thing you can do is to keep close to the Church. You will best learn to love God if you will do that. The Church is to be like a home to you. You are becoming a fully privileged member of the Family of God by your Confirmation; you will have a right to all the joy and strength that the Church can give.

And that is no small thing; for the Church is the place where you share with all the great Saints. You have a seat united with them, they pray for you, and encourage you.

But more than anything else, the Church is the place where Our Lord Jesus assures you of His Love for you, and gives you what is called His Grace. If you go to Church regularly; and to the Holy Communion; and to receive your absolution; and to be regularly instructed, you will find that the “Love of Jesus” is not a mere phrase, but is a real, and holy, and very happy thing.

So keep close to the Church. Join the Guild that is suitable for you. Make close and true friends with the Clergy, who are anxious to be of use to you—and be regular in your public and private prayers. Don’t put your little book away in a drawer, but use it every day and every Sunday. Put away all timidity about tomorrow. God Himself has called you—it’s His doing more than yours, and He has called you because He loves you.

Go to the Service with the eager faith and hope of a little child. That is far the best way. And when you are confirmed, don’t worry about your feelings—it is in your spirit that it all takes place, not your senses. God will be with you, and you need fear nothing. May God bless you very richly, and keep you to persevere.

Yours affect’ly [affectionately] in our Lord,

A. E. Laurie

At one point, I become excited over some ephemera that fall out from between pages of a book full of Laurie’s sermons, which were reconstructed and published shortly after his death. The book is heavily worn, missing its spine. The bits of paper tucked inside are covered with notes clearly in a minister’s hand, including scribbled points on the back of a letter from a distraught woman in his congregation. Was this handwriting Laurie’s? I would walk away assuming so, but on closer examination later I realized that was impossible. One scrap has the date “1946” scribbled on it, and another has a reference note to the Laurie sermon collection. I now wonder if these are actually in the hand of Laurie’s successor as parish Rector. I think of the compassionate care apparent even in the sketchy outline for his reply to the distraught woman, and I think how satisfied Laurie would be that his legacy was carried forward so faithfully.

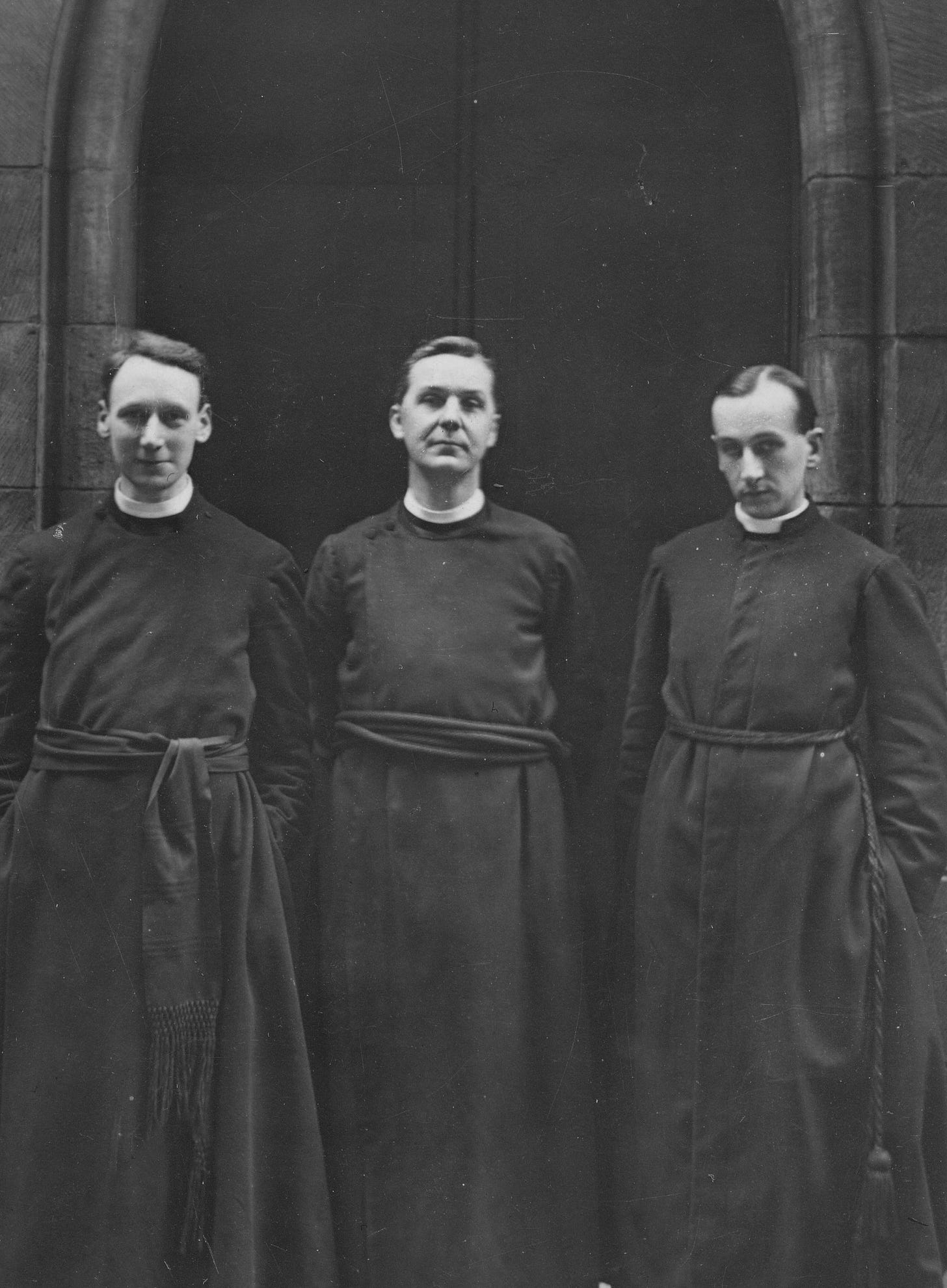

Another picture from the binder, below, shows Laurie with two fellow Old St. Paul’s ministers. The one on the left is Gustav Meister, a young priest who also served and died as a chaplain. The two men were separated for the war, so Laurie heard of his death secondhand, but it still shook Laurie profoundly that such a promising young life should be cut short. He pays moving tribute to Meister in one of the war letters, describing the modest heroism that marked his last hours. Meister had volunteered to sleep in a more exposed position so that other men could take the limited space with better protection. When the shelling came, they were safe, but he was killed. Laurie tried three separate times to fight his way to the place where Meister was buried, but Germans surrounded the area, and he had to turn back defeated.

At no point, of course, does Laurie leave a record in his own words of the heroism that would earn himself two Military Crosses. In the binder, I found a copy of the paper where one of his single-paragraph citations appeared, a thumbnail sketch among thumbnail sketches. Like Luke the evangelist, his biographer had to piece fuller stories together later from other reliable sources—at the Somme, how he continued collecting the wounded in No Man’s Land even after the rest had fallen back; at Poelcappelle in the Passchendaele, how he ignored orders to stay behind and spent 24 tireless hours directing stretcher bearers in the field. Staggering into an aid station afterwards with a shallow back wound, he was only persuaded to stop and rest by the threat that he could be sent down as “a real casualty.”

Gustav Meister’s name is carved with the rest of the parish’s Great War dead on the wall of its Warriors’ Chapel. Commissioned by Laurie and built with money painstakingly scraped together over years after the war, the chapel is a stunning achievement relative to the congregation’s location and means. Poor as they were, Laurie held his flock to a high standard of giving, instituting an annual “Sacrifice” system where everyone’s individual offerings were brought forward and poured into a communal pile. In this way, nobody but the individual congregant knew what he personally had contributed. Thus trained, the parish did the impossible and raised what was necessary to fund the memorial. Decades later, more names would be carved to honor the fallen of World War II—which, in the kindness of God, Laurie would not live to see.

For the centennial of World War I, Peder and the Old St. Paul’s archival team tracked down as much biographical info as they could on all the names, then presented their findings in full-color, limited-edition magazines year by year. They couldn’t quite place every name, but they came as close as they could. Unfortunately, Peder couldn’t locate the digital masters for most of the issues. He copied over the only one he found, and also sent me home with two spare physicals. I snapped pictures of the issues with no duplicates that I had to leave behind. I’d like to re-type the information into an appendix for my project, ensuring that it isn’t lost.

Before I knew it, the whole afternoon was gone. I chided myself later for not being as efficient as I could have been, for not cross-checking closely enough to see what had and hadn’t already been digitized so that I could capture it. But I saw what I came to see. I carefully collected the books I brought myself—my own copies of two volumes of Laurie’s sermons. Peder picked up the slimmer one to leaf through, saying not even he has a copy of it. Later, Google tells me there are no copies available anywhere in the world for purchase. I plan to add it to Open Library.

I will see Peder again when I attend mass at the parish on Sunday. But for now, it is goodbye. At the door, he offers me a hug, and kisses me on the cheek.

Fascinating story.

sorry to focus on something un-central, but you mention that you 'scanned and uploaded' his biography to Open Library. I love this idea of giving old books new access. Can i ask how you scanned it?