Religion, Revisited

Reviewing Ross Douthat and Charles Murray

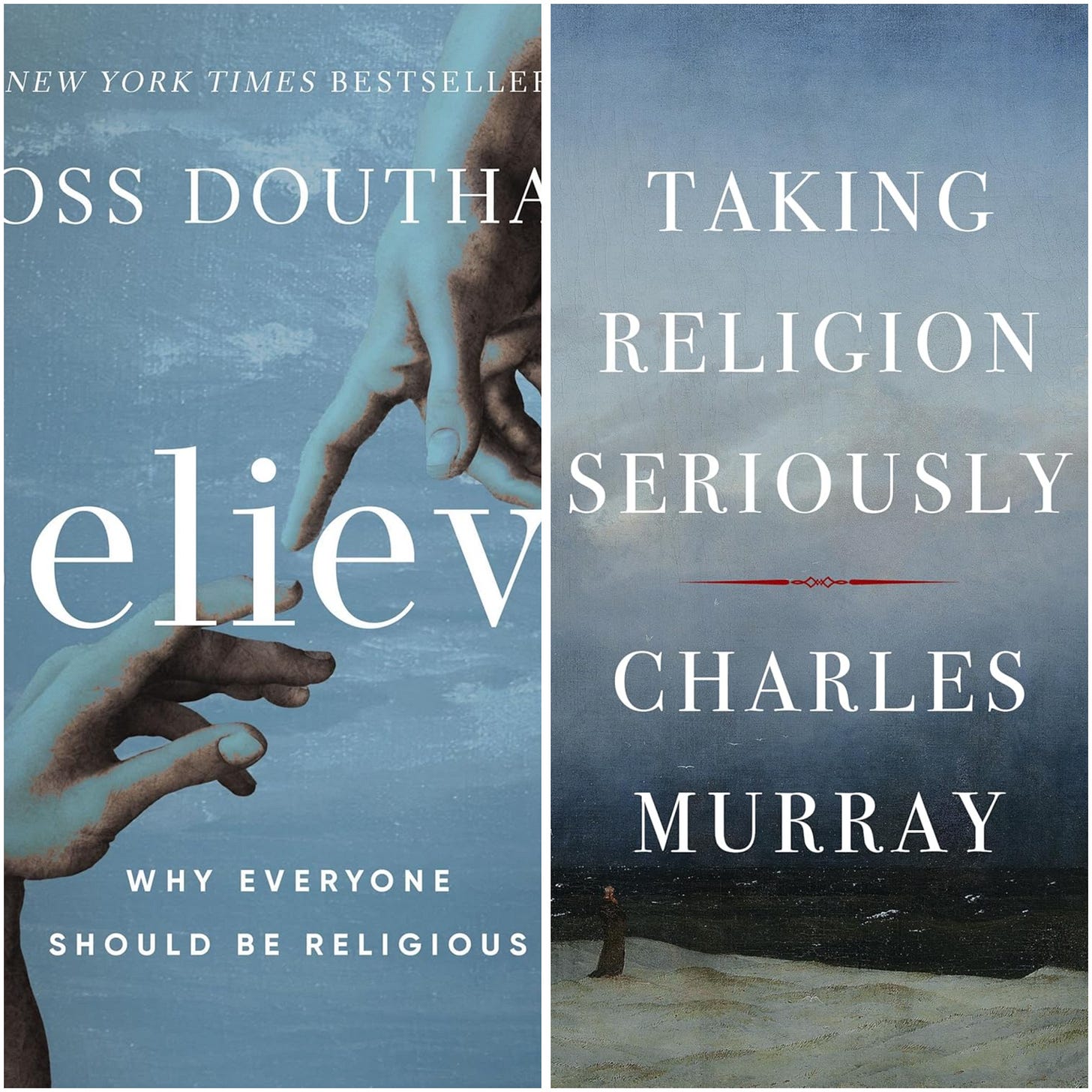

One of the most buzzed-about books of 2025 has been Ross Douthat’s Believe, which ambitiously pitched itself as “a blueprint for thinking your way from secularism into religion, from doubt into belief.” In a world where people tend to see religious belief as an option, Douthat pressed the point that it’s actually an obligation, and that the spiritual seeker owes it to himself to take up the serious work of seriously studying what’s on offer. Little did he know that a fellow public intellectual had begun taking his advice some 30 years before he gave it.

Later this year, social scientist Charles Murray (of Bell Curve fame) released his own uncannily similar book, Taking Religion Seriously. Though Murray approaches his readers as a man still in transition, presenting as it were field notes from his spiritual quest, there are many points of convergence with Douthat’s evangelistic blueprint. So many that as I close out the year here at the Stack, I thought it could be fruitful to offer my readers a double review. Among other things, this is a clever way to paper over the fact that I requested and was generously provided with a free copy of Douthat’s book well in time to review it back when everyone else did. (A positive review was not required, etc.) I had no idea Murray was going to release his book and give me this convenient way to circle back, but we can pretend I did.

Long-time readers will know why I was especially keen to dig into both these books, but as a very short introduction for any newcomers, religion has been a “beat” of mine for a long time, with a special interest in the intersections of religion, philosophy, and apologetics. Both my parents, though not widely known, are philosophers who have quietly contributed groundbreaking scholarly work in these fields. To my surprise and delight, it turns out both Douthat and Murray have independently discovered my mother’s work in New Testament studies and given her a nod in their chapters on the reliability of the four gospels. There are many things I could say about the current state of evangelical apologetics, not all of them good, some of them very bad in fact. But it’s gratifying to see my parents’ contributions start to break into mainstream religion writing.

These two books arrive at a moment when apologetics in general seems to have fallen out of fashion in religious discourse. There is a prevailing sense that everyone is moving on from the “modernist wars” of the religion-atheism debates with Dawkins, Hitchens and friends, that it’s time for a new paradigm entirely. Non-believers are happy to adopt a more irenic approach, while some believers downplay the helpfulness of a rational appeal. This three-way dialogue with Rowan Williams, Alex O’Connor, and Elizabeth Oldfield is a representative sample. Oldfield echoes religion writer Karen Armstrong, who describes religion as not “something that people thought but something they did.” All these pointy-headed debates have been missing the point, Oldfield thinks, and what an atheist like O’Connor really needs to do is just stop overthinking things, join a church, and immerse himself in the practice and the ritual. “Let go and let God,” as it were.

But Douthat demurs that “you can also do some weighing up and reasoning in advance,” actually, that the magisteria of faith and reason can and should overlap, actually. We may not always behave rationally, but we are still the rational animal. Thinking about faith “can make faith feel less impossible and more sensible, less absurd and more essential.” This is particularly useful for those who lack the gift of spiritual sensitivity. Murray self-deprecatingly identifies as one such insensitive soul. He realizes his methodically cerebral approach might seem a bit dry to some readers, but he can’t help it. He’s a methodically cerebral kind of fellow, and this is the only way he feels able to tackle these questions. He doesn’t claim any special expertise in matters religious, he’s just a layman showing his work as he goes, and he encourages you to do your own.

I, for one, say more power to Charles. I also say kudos to Douthat for encouraging his readers that thinking about religion isn’t an inscrutable exercise reserved for a handful of elite intellectuals. The tagline for my mother’s YouTube channel is that she labors to “make common sense rigorous.” Though that work can get quite technical, she is formalizing intuitions that are accessible to everyone. Both Murray and Douthat really get this, and it’s the great shared strength of their books.

Another shared strength is range: Murray and Douthat have read widely and offer reasonable summaries of the hot debates in areas as disparate as physics, neuroscience, and biblical studies. These summaries could be qualified and nuanced, which I’ll get on to, but they serve as engaging primers for someone only beginning to give this stuff much thought. Moreover, neither author is squeamish about challenging consensus. Murray, of course, was famously excoriated for his work on IQ differences, and Douthat in his own way has danced on the edge of respectability with his writing about health and medicine in his Lyme disease memoir The Deep Places. Neither has a temperament that’s inclined to accept Official Knowledge with no questions asked.

That “honey badger don’t care” mentality has served them both especially well in their study of biblical scholarship, New Testament studies in particular, where they correctly perceive that the revisionist case is vastly overstated (though Murray pauses his argument in a puzzling place, which I’ll come back to later). They independently converge on some of the strongest arguments for the four gospels’ substantial reliability as historical documents, including undesigned coincidences (where my mother’s first book, Hidden in Plain View, is name-checked), accuracy in minute details of culture, geography, etc., and other qualities marking the texts as memoir, not legend. They intuitively suss out the sheer flimsiness of certain skeptical arguments, the compulsive substitution of convoluted explanations for simple ones. (Another excellent short book they both recommend for further reading is Peter Williams’ Can We Trust the Gospels? To this I would add my mom’s most recent book, Testimonies to the Truth, which further deepens and broadens these arguments at an accessible pitch.)

While I wish that sociology didn’t loom so large when it comes to truth-seeking, I can’t deny that sociologically it matters when writers of Murray and Douthat’s status give readers this kind of intellectual permission slip to question received wisdom. Both of them belong to, as Murray puts it, “the tribe of smart people.” Not that Murray exactly means this as a compliment to said tribe. In context, he is frankly confessing that it kept him in an intellectual bubble for decades, and that part of him still worries about getting kicked out of the club. Still, for now, mainstream outlets are expected to pay attention when someone like Murray writes a new book.

This status is rarely afforded to evangelical Christians, and the odd one who does break through is generally perceived as something of a snob—often, I’ve argued, with reason. When Murray occasionally drops the name of an evangelical in his orbit, it’s a name like Peter Wehner or Francis Collins, neither of whom is popular in more conservative circles. One could imagine how Murray’s journey might be cited by such voices as a successful case study in the importance of placing “smart people’s Christians” in a position to recommend C. S. Lewis books to elite agnostics. But I choose to simply rejoice that the gospel of C. S. Lewis was preached, and that just as Lewis gave Murray his own permission slip, Murray is now eager to pay it forward.

There still remain some areas where both authors more or less go with the grain. For example, both seem content to accept the evolutionary paradigm in broad outline, although they propose it’s not a complete account of reality. Murray believes evolutionary psychology has its uses, yet it failed to give his wife a satisfactory account of why she loved their daughter “more than evolution requires.” He concludes that no evolutionary just-so story can explain the emergence of pure agape love. Douthat meanwhile argues that the evolutionary process itself requires “a law-bound material substructure,” which in turn requires a lawmaker. This loose end remains despite his concession that “Darwinism established, with uncertainties around the edges of the theory, that an algorithmic process running over an extended period of time can generate increasingly complex and increasingly diverse machines made of cells and atoms. From small acorns, mighty trees; from the building blocks of life and the complex pressures of Earth’s environment, stags and fungi, orcas and armadillos, praying mantises and human beings.”

I myself don’t concede that Darwinism established anything of the sort, and while I’m not a young earth creationist, I think that when it comes to human origins in particular, these questions have theological stakes. But I understand why Douthat is uninterested in arguing the point. And I can see why both he and Murray, like many others, are particularly drawn to arguments like fine-tuning, which precedes all the messiness of the Darwinian debate by focusing on the narrow range of life-sustaining possibility for various universal constants. It’s a tempting line of argument that won’t create any record-scratch moments at cocktail parties (not that I think Douthat and Murray are angling for cocktail party invitations, I’m just noting why this argument persists while bolder arguments from design struggle to gain elite purchase). However, at the risk of being a party-pooper, I should mention that there is a technical objection to fine-tuning which has never been satisfyingly resolved in the literature. Compounding the awkwardness, this objection was actually raised by none other than my apologist parents, as joint work with mathematician Eric Vestrup. But my mother has proposed a few potentially fruitful ways the conversation could still proceed, in a paper available here for anyone curious and nerdy enough to have a look.

Both books also devote a generous amount of space to what could be dismissively described with the catch-all term “woo”: near-death experiences, psi phenomena like telepathy, “close encounters” of the spiritual kind, and assorted other spooky stuff. Murray and Douthat seem to relish how such things make their sophisticated colleagues squirm. I’m typically inclined to suspend judgment until I can examine the details, where the devil tends to (metaphorically) lurk. Obviously, I agree with Douthat that evolutionary just-so stories can’t explain NDEs, but then I believe they can’t explain anything! It seems to me a plausible third way that our brains are divinely designed, but our brains are just weird, man, and NDEs are a form of exceptionally weird qualia. Still, like Murray I’m intrigued by certain specific NDE cases with empirical tiedowns, as well as case studies of terminal lucidity—dementia patients struck with sudden clarity in the last moments of their life. These cases along with the NDE literature convinced Murray of mind-body dualism. But I would argue materialism can be put to bed by introspection alone, no “field work” required. Douthat’s chapter on the hard problem of consciousness very nicely drives this home: We confound materialism every moment, with every thought we think.

Douthat points to the resilience of “woo” in the modern age as a defeater of Hume’s prophecy that such accounts would decline along with the decline of organized religion. They seem, if anything, to have multiplied. But I think this was sociologically predictable. People are perennially curious about the paranormal and crave the thrill of being in some sense “in touch” with “the beyond.” With the decline of religious institutions comes a natural spike in such experimentation/exploration outside institutional boundaries. As well, I actually think people’s minds will more quickly leap over natural explanations to vaguely defined “woo” if they don’t already have a well-formed theology of God, angels, or demons, or a sense of such beings as agents whose actions aren’t entirely random. Most poignantly, grieving people with no firm account of the soul or the afterlife will grasp at any dubious wisp of “supernatural” comfort, or gullibly wander down rabbit trails like reincarnation.

It’s also worth noting that even in our “disenchanted” modernity, woo isn’t necessarily out of step with Official Wisdom. For example, concepts like “energies” and “chi” are taught in medical classes. There is if anything a greater than ever official openness to, let’s say, non-threatening woo. No one is out to take your “spiritual experience” away from you, provided it doesn’t crystallize into anything too uncomfortably specific.

But Douthat proposes that some encounters are precisely of that uncomfortably specific kind that refuse to be explained away. Further, he proposes there is something in this body of experience to make atheists and Christians alike uncomfortable. As a Christian, of course I believe God is living and active and capable of revealing Himself in the world as He sees fit. I likewise believe that Satan and his minions will make themselves, let’s say, available to those who very unwisely seek them out. Yet Douthat pushes a step beyond even this, arguing that “the orthodox Christian (or any believer in the specific truth of a particular religion) has to assume…that the divine meets us where we are, even using the imagery and symbolism of other faiths.” When he pitches his book as an argument for “why everyone should be religious,” he means exactly what he says: Committing to any established religion, not just Christianity, is a good thing.

This is my biggest point of departure from Douthat, and indeed from how many modern Catholics approach interfaith dialogue. It’s one thing to trust that God in His infinite wisdom will deal mercifully with those who die having earnestly sought The Good while never encountering Christianity. Like Douthat, I’m drawn to C. S. Lewis’s character Emeth in the last Narnia chronicle, a young pagan who is graciously welcomed into Aslan’s kingdom after spending his life in service to the vulture-demon god Tash. But I don’t think Lewis intends to convey that it was Emeth’s pagan religious practice per se which prepared him to receive the goodness of Aslan. Rather, there is something singular about Emeth’s personal character, about his integrity and his desire to know the truth, as hinted in his name (“truth-seeker”). That purity of heart is what ultimately allows Emeth to see God—in spite of his devotion to the Tash cult, not because of it.

Douthat stresses that he’s not encouraging people to join the next vulture-demon cult they bump into. But he thinks there’s a degree of security in ancient traditions with repositories of wisdom for guiding people through the spiritual wilderness. Though he seems to make a distinction between the great world religions (Buddhism, Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, Christianity) and the tribal traditions of Africa, Latin America, or American Indians. I’m not precisely sure why, since the latter traditions are themselves quite old, with shamans happy to “guide” people in the practices. In any case, I’m much warier than Douthat about the spiritual risks of wading deeply into even those traditions that have gone through more civilizational refining. I’ve pointed before to the story of Michael Sudduth, a scholar who grew up Christian but was drawn to Hinduism and believed he’d had a personal encounter with Krishna. Whatever he actually encountered, I’m quite sure it was not the true God in disguise.

Emeth’s people, the Calormenes, are obviously modeled on Muslims. And speaking of Islam, it’s also worth noting that when one listens to testimonies of Muslim to Christian conversion, they don’t sound like stories of “divinity meeting them where they are,” in the form they’re most likely to revere. Quite the contrary: If one takes such testimonies at face value, Jesus seems to be in the business of showing up and explicitly announcing himself in dreams and visions. The recipients of such visions are then typically faced with a stark and dangerous choice about how to proceed.

Douthat is of course writing in a pluralistic American context, to a target audience with the luxury of exploring various religions at will. But he’s boldly proposed elsewhere that pluralism is the future of the globe. I have no such confidence, not only when I look at the persecution of Christianity in Muslim countries, but also when I look farther East to China or India. In conversation with Eric Metaxas, Douthat opines that there’s room for friendly concourse between Hinduism and Christianity. It’s a lovely idea in theory, but in practice, Indian Christians are violently suppressed under Hindutva. Churches are raided, worshippers are arrested, and missionaries’ lives—Western and indigenous alike—are constantly threatened. I’ve worked with one missionary for years who knows this firsthand. Another came to a retreat in my town once, then waved goodbye at the end with a matter-of-fact, “Well, see you all next year, if I’m alive.” The people he hopes to reach with the gospel see him as a threat. I submit that in one sense, he is. In countries where persecution rages, where all the comforts of Western pluralism are stripped away, we see the purest clash of truth and falsehood, primeval darkness shrieking out in recognition of primeval light.

Even here in the comfortable West, people must count the cost of commitment. Douthat wants to encourage his readers that there are enough theological stepping-stones between the great world religions, people needn’t feel “locked in” to the first one they explore. You could try something that works for a season, then find that you’re more drawn to something else and move on. But in life, such things aren’t always so simple. Even within a particular tradition like evangelical Christianity, the process of switching churches can be fraught with social awkwardness, as ties are broken and support networks are lost. How much more complicated is the process of picking up sticks and moving to another religion entirely, particularly if there are other loved ones in the picture?

I’m especially sensitive to this problem when it comes to the gulf between little “o” orthodox Christianity and the various denominations wearing Christianity as a skinsuit. Douthat gestures to these in another chapter addressing common stumbling blocks like the Christian sexual ethic. If the reader is hung up on this, well, there are “churches” full of people eager to let you know that this isn’t a problem at all. While Douthat is on the record as a conservative Catholic who believes conservative Catholic things about these issues, for the purposes of this book he’s doing a delicate dance. He argues that, to put it mildly, it’s not unreasonable to imagine God might care what we do with our genitalia. And yet, if a reader grew up in a mainline church that gave away the farm on sexual orthodoxy long ago, he won’t outright say it’s a bad idea for that reader to go back to that church as a starting point for religious exploration. Myself, I would submit that there is, if anything, an extra danger in committing to such denominations, since they lull people into a complacent assurance that they alone have found the true and enlightened form of Christianity. Again, I would point out the cost of moving to embrace orthodoxy once you’ve already bound yourself—perhaps even with “marriage” vows—to heresy.

Charles Murray’s roots are Presbyterian, which he returns to in memory as he tries to grapple with the theological consequences of all his exploring. But already by the 50s, when Murray was a child, a good evangelical would say his church was less than theologically sound. While trying to get a handle on the Incarnation, his mind goes back to an analogy made by the reverend who prepared him for confirmation: You can scoop saltwater out of the sea into a jar, and though the water is the same, it’s no longer “the sea.” In the same way, Jesus isn’t God. He’s just as much of God as you could get in a human “jar.” This is still helpful for Murray, who’s deeply uncomfortable at the thought of overly “anthropomorphizing” God. Even though he’s intrigued by C. S. Lewis’s Trilemma, intrigued by the resurrection, and forced to admit that Christ had some kind of “special relationship” with God, that fundamental discomfort leads him to balk at a full-throated creedal declaration.

Moreover, and perhaps related, for all his deep reading on the reliability of the gospels and the scrupulousness of their authors, Murray concludes that the Nativity story is a charming legendary accretion. Even though he’s been persuaded that the gospels are the work of writers trying to get even small details right about Jesus’ life, teachings and passion, he doesn’t appear to see how that cumulative case for reliability is a rising tide that lifts all pericopes—that once you’ve amassed a body of evidence for Matthew’s comprehensive trustworthiness, or Luke’s, the probability that they would casually embellish something like the birth narratives will plummet.

Does this mean that I, as a conservative Christian reader, must say in that case Murray’s journey has all been for nothing? That if he was going to come this far, only to stop before grasping the very nettle of the gospel, the “Before Abraham was, I AM” linchpin on which Christ’s whole atonement and resurrection hang, then he might as well have not bothered at all? I don’t think so. I think that Murray is earnestly seeking the truth, and he’s been seeking it in the right place. Without knowing it, he’s taken up Douthat’s challenge in the most spirited and meticulous way he could. I would simply encourage him to keep going, and to keep questioning some of his presuppositions. When he says that he believes God is as unknowable to us as we are to our dogs, I would challenge him to consider what it means that we are made in God’s image. It is certainly true that our minds boggle when we try to comprehend God’s full essence. Yet the mysterious and terrifying truth remains that we alone among all earthly creatures, from the richest king to the poorest beggar, have been granted a spark of the divine. We alone have eternity set in our hearts. We alone love our children more than evolution requires.

Douthat, for his part, confesses that Jesus makes him uncomfortable. But he believes this is a good thing. By personality, he is naturally conflict-averse, and he instinctively cringes at the thought of seeming to push people too quickly towards one conclusion or another. He would like to tell you that you have all the time you need, all the time in the world. But then he would have to ignore the urgent words of that unsettling Galilean rabbi, those parables of condemned goats and foolish virgins and men cast wailing into outer darkness.

At night, when Murray has insomnia, he tries to let his mind wander fruitfully. One night, he was thinking about what it would be like to meet the great religious figures of the past. All would fascinate him, all would command his respect. Yet, “Unbidden, it came to me that I would treat Jesus differently. With reverence.”

A master of men was the Goodly Fere,

A mate of the wind and sea,

If they think they ha’ slain our Goodly Fere

They are fools eternally.I ha’ seen him eat o’ the honey-comb

Sin’ they nailed him to the tree.

Thank you for this thoughtful review. The testimony of honest thinking unbelievers is powerful. The struggle of a rigorous man with faith is understandable. May God grant Mr. Murray that light while it is still Today.

I have less sympathy for the professing believer who seeks to temporize what is uncomfortably clear in Scripture. May God protect those who seek Him.

The era of the individual is over. We must tribe or die. And where two or three gather together in the name of the tribe, the woo may be among them.